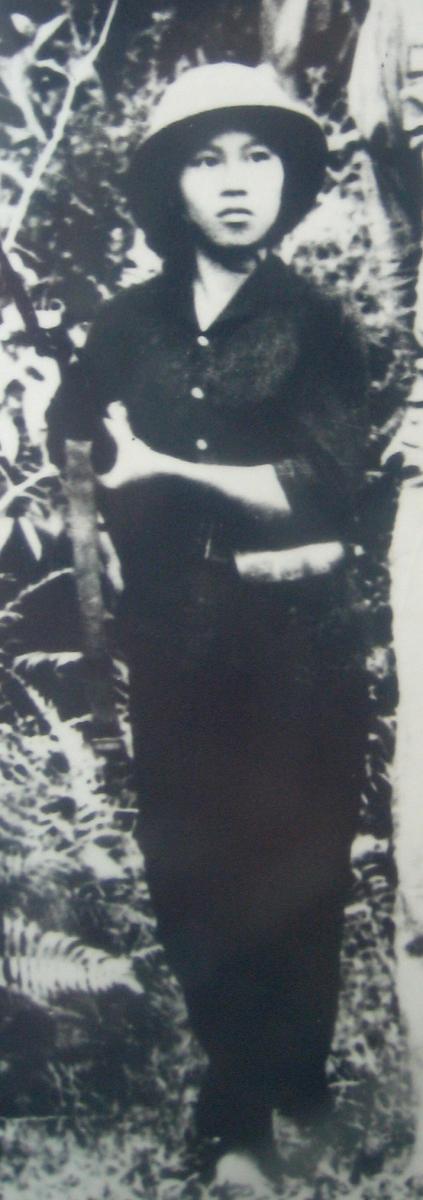

Dr. Marjorie Nelson

Jill Richards, Marjorie Nelson and Nguyen thi Xuan Lan, Quang Ngai, Vietnam, circa 1967-1968

Photo Credit: Marjorie Nelson

Jill Richards, Marjorie Nelson and Nguyen thi Xuan Lan, Quang Ngai, Vietnam, circa 1967-1968

Photo Credit: Marjorie Nelson

Dr. Marjorie Nelson was a member of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) team in Quang Ngai, South Vietnam, serving as a doctor at the Quaker Rehabilitation Center. A 1970 report from the Center noted that nearly 90% of the injuries treated at the center are war-related, with landmines and artillery being the principle causes. Of these injuries, 75% were leg amputations.

During the Tet Offensive in 1968 Dr. Nelson and her friend Sandra Johnson who was serving in Vietnam as an International Voluntary Service worker, were taken captive by the National Liberation Front of Vietnam. These excerpts from Dr. Nelson’s report to AFSC recount her experiences with the NLF during the fifty plus days she was a 'guest' of the Front.

Surviving many days and nights of walking through the jungle, blisters and amoebic dysentery, Marjorie was grateful for the care she received from her captors until her release on April 1, 1968.

On the 9th of February we were officially registered as Prisoners of War. We were told in English that we were going to be taken to the mountains and that when there was peace, we would be returned to our families. I therefore assumed we were in for a long stay! We left that night and walked most of the night before resting for a few hours at a small village in the hills. The next morning we set out again after breakfast and walked until late afternoon to a jungle camp on a mountainside. I was so exhausted after this long trek that I didn't move much for the next two days.

The evening we arrived a young soldier appeared and again questioned us in English about our names, professions, the agencies for which we worked, etc. After answering his questions I in turn asked him his name. He was momentarily nonplussed but then replied that his name was Nam. He turned out to be the cadre responsible for the care, interrogation and indoctrination of the prisoners in the camp. We came to know him quite well as every afternoon he visited with us for a few minutes,--sometimes talking about politics but more often about other topics such as teaching, medicine and life in Vietnam.

Sandy and I spent about ten days at this camp living in a jungle house with a Vietnamese family group. About the third day we were told to go up and eat our meals with the other prisoners,--it was at this point that we first knew that there were other American prisoners. Approximately 25 American men, both civilians and military personnel assigned to work in Hue, had been captured and brought to this mountain camp.

Countless times I was thankful for the effort I had put into Vietnamese language study during my four months in Quang Ngai, for being able to communicate, however simply, in Vietnamese was invaluable. We spent a great deal of our time in the mountains simply talking to people--mostly soldiers. We were the first American women they had ever met so they asked us many questions. First came the usual ones for a Vietnamese: "How old are you?" "Are you married?" "Do you have a sweetheart?" "Are your parents living?" "Do you have brothers and sisters?"

Then, always, came the question: "What do you think about the war?"

Finally they would ask if we were homesick and if we wanted to go home. To the latter I always answered "not yet" which surprised them. My answer afforded an opportunity to explain why I had come to Vietnam and that I was willing to stay and work. I repeatedly offered to work either in Hanoi or in a liberated area village in the South if I could be of service but their answer always was either "The life is too hard for you here," or "We have enough Vietnamese doctors and nurses. We don't need your help, thank you."

|

|

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons |

After a few days at the first camp, Mr. Nam told us that we Americans would be moving soon to a camp about ten days walk away where the facilities would be better. Before we left he secured boots or some type of foot gear for all of us who needed it. He also gave Sandy and me a plastic square which we used as a ground cloth. Setting off around the 20th of February with Mr. Nam and five guards, the group of about 25 prisoners traveled and camped in the mountains for six days.

As it was rugged terrain, most of us acquired a few blisters and were tired at the end of each day. Thus, much of the work of setting up camp, starting a fire and cooking fell to the guards. However, we were never too tired to talk or sing after supper, so I could at least look forward each day to the evening in camp.

During my two months in the mountains I met many NLF soldiers. I was impressed with their dedication, cheerfulness, and enthusiasm. They are a proud people--determined to be self-reliant and self-sufficient. I was continually surprised and delighted with the friendliness and thoughtfulness shown to us. On the evening of the sixth day Mr. Nam and one of the guards came to where Sandy and I were sitting and announced they were going to eat with us. This was very unusual for we had never eaten with the guards before, and we enjoyed it very much. After supper, Mr. Nam sat with us for a while and finally he said, "Tomorrow I won't be going with you. We will be separating." I was quite disturbed at this announcement for I both liked and trusted this man. I felt confident that as long as we Americans were entrusted to him he would do his best to see that we were well cared for. He then took a small bit of cotton from his wallet and unwrapped it revealing a small gold and enamel medallion which he gave me as a keepsake from him. In addition he asked that I write to his sister in North Vietnam and give her news of me after my eventual return to the U.S. I was deeply touched by these gestures which confirmed my feeling that significant communication had occurred in spite of cultural, ideological and language barriers.

We were told about the middle of March that we were going to be released as soon as arrangements could be made.

We were also told that the soldiers were making us souvenirs --combs made of aluminum taken from napalm cannisters --to take with us.

We received a lecture on the desirability of using aluminum to make combs instead of napalm cannisters, to which we heartily agreed. Shortly after that, at the order of the camp commander, Sandra and I were given a farewell party by the soldiers. As we gathered around a small lamp in the bomb shelter, two soldiers brought in a basinful of fresh peanut brittle and canteens of hot tea. We ate this while the soldiers asked us questions about life in America. In addition to the usual questions I mentioned above, they wanted to know how we came to Vietnam, as well as facts about farming, agriculture and wages in the U.S.

June, 1968, Marjorie Nelson, Quaker Service Vietnam Report # 17. For a more detailed account of her experiences during her captivity, see: <http://afsc.org/story/taken-prisoners-viet-cong>

Reflections on Vietnam, 2008 (Friends General Conference)

|

|

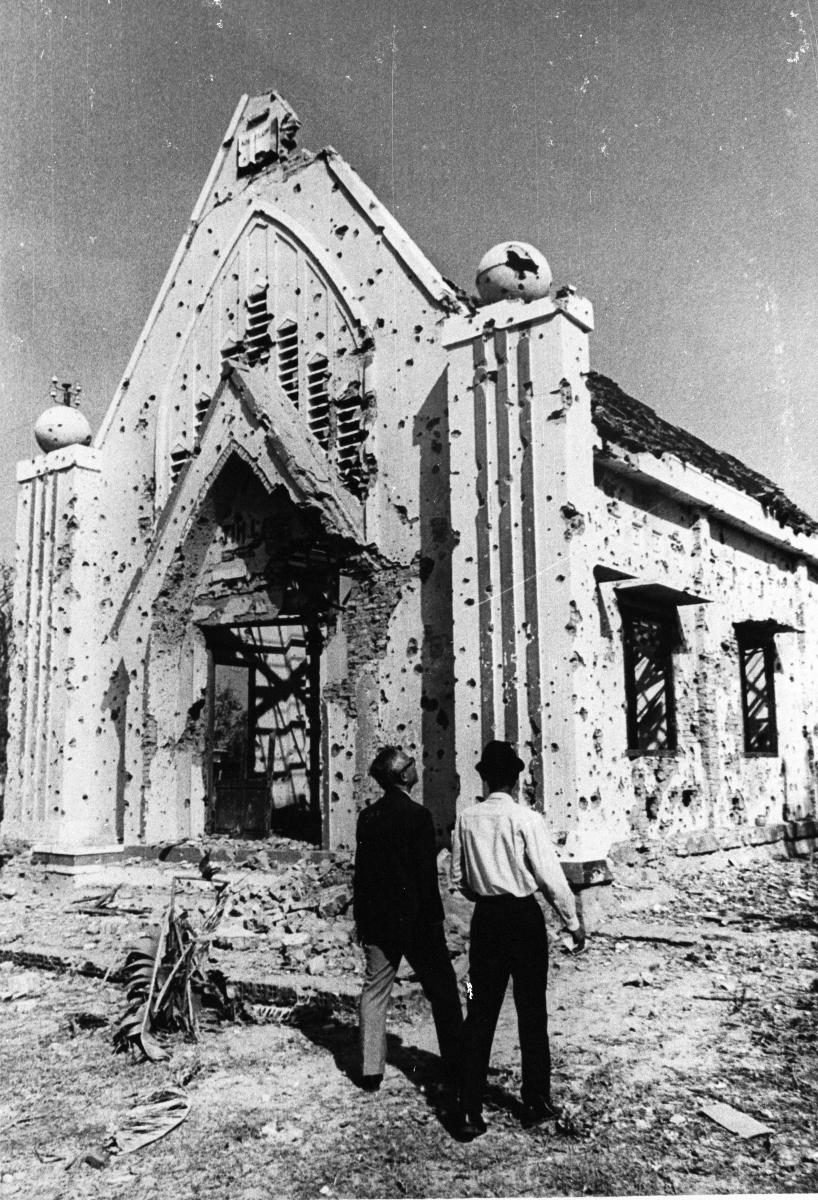

Pastor Tran Xuan Hi (left), looks at his church which was destroyed during the Tet Offensive, April, 1968, Thu Duc, Vietnam. MCC Photo by Lance Woodruff |

I remember a conversation some years ago with a minister of Calvinist persuasion who asked me to explain Quaker views. I replied that Friends believe that alongside a person's immense capacity for evil, there is an equal potential for good often referred to as "that of God" in every person. Rather than resort to violence Quakers appeal to people by word and deed, to heed inner promptings of the Spirit of God and do good rather than evil. The minister looked at me rather quizzically and said, "Don't you think you are in danger of underestimating the power and influence of evil with that approach?" "No," I replied, somewhat startled, "I don't think so." The crucifixion of Christ testifies to what may happen when one is steadfastly loyal to God's calling. There is no guarantee of safety or success in the conventional sense in this approach toward violence and a person's capacity for evil. However, the resurrection of Christ stands as God's testimony and promise that ultimately the way of sacrificial love will prevail over the powers of evil and darkness.

As I reflected further on that minister's question my mind turned to many scenes I witnessed and stories I was told during my two years of service with an AFSC medical team in Quang Ngai, Vietnam in the late 1960s.

Our project was located six miles from My Lai. We treated at least one survivor from that massacre. Vietnamese friends told me not only of that event but of five similar incidents perpetrated by American or Korean troops in our province alone. I saw children injured by NLF rockets which exploded near their orphanage. I treated patients in our rehabilitation center who had extremities blown off by land mines planted by both sides in that conflict. Do I underestimate the power and influence of evil? I think not.

And yet I also saw American GIs caring for wounded Vietnamese in the hospitals. On their days off they would spend their time making equipment for our patients to use in the rehabilitation center. I saw a young Vietnamese officer adopt a little orphan amputee patient of ours although he was no relative. And in 1968, taken prisoner by the NLF in the Tet Offensive, I experienced good treatment and tender concern by "the enemy." When I fell ill with dysentery, a North Vietnamese doctor walked for several hours through the mountains to my camp to treat me. The soldiers collected from their meager belongings such things as powdered eggs, a little sugar, and a can of sweetened condensed milk which they gave me "to help you regain your strength." The cook of the camp started rising at 4:00 a. m. to catch small fish in the stream to supplement my rice and vegetable diet. No one else in the camp had meat. Never in my life have I been more uplifted and sustained by a sense of the power and loving presence of God than in those two months in the mountains of Central Vietnam. Yes, throughout the years, Friends have found repeatedly that reaching out to "that of God" in others can be very creative in situations of conflict and violence.

See also: Taken Prisoner by the Viet Cong (AFSC)

Education and Service Projects in Vietnam, Feb 1, 2011, Friends Journal