Roger Marshall

|

|

Roger Marshall, Physical Therapist Photo Credit: American Friends Service Committee |

REPORT

-by Roger Marshall, Prosthetist, Quaker Rehabilitation Center, Vietnam, 1969

Anyone who spends, say, more than a year in Vietnam runs into the danger of becoming immune to shock. One’s first few months here are often a series of stomach-turning revelations. Then, after a while, particularly if you work in the medical field your senses become dulled. You can look at a gaping wound, a crippled body a legless child, and no extra adrenalin pumps into your veins and no anger rises up. A new case comes in, a shattered body or a numbed and paralyzed mind, and you take on the job of repairing it with hardly a flinch. After all, it's just another case like you have seen a hundred or a thousand times before. Then, one day, a patient turns up and you notice something different, and that old feeling which you thought was either dead or dying suddenly wells up inside you.

Today I had that feeling. It was a mixture of anger, frustration, compassion, call it what you will, and it was caused by the appearance at our Rehabilitation Centre of a thirteen year-old boy named Vo-Han.

I was sitting at my desk trying to evaluate the work we had turned out over the past month, when Vo--Han was brought in on a wheelchair. I realized I would not get that part of my work completed that morning. Vo-Han was brought in by a U.S. Army captain, a U.S. soldier, and a Vietnamese ARVN sergeant. There was nothing unusual about that nor about the fact that Vo-Han had both legs amputated below the knees.

|

|

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons |

What I did notice was that he was wearing a U.S. Army uniform, complete with name tag and flashes on his shoulders, again not too unusual, as the Vietnamese often wear a confusing variety of clothes and uniforms. In this case, though, Vo-Han was obviously a child of no more than fourteen years old. I suddenly got the feeling that this was an unusual patient. The Army captain seemed to be uneasy, and I instinctively felt a strange sensation of aggression towards him and the other two soldiers.

The captain introduced himself and told me Vo-Han, who was in fact thirteen years old, was employed by the U.S. Army as an interpreter. He had been out on patrol with a U.S. unit some five months ago and had detonated a VC mine. It was at this point that I realized what the setup was. I had heard about such children being employed by U.S. patrols but I had never before met one.

I think that the conversation between the captain and myself should not be repeated. I will admit that I got very angry, and when I questioned him or the morality of taking a thirteen year-old child out on a combat patrol he countered by saying that it was no less immoral to be blown up by a mine, that he also had two other children of eleven years old doing the same work, and that they were all volunteers earning $40.00 a month, their salary being paid out of the pockets of the Gl s in the platoon at a cost of no more than $2.00 for each man per month...

Vo-Han lives in the village of Son-Quang in the district of Son-Tinh, a few miles north of Quang Ngai. He has a sixty-two year old father a forty-two year old mother, three brothers, nine, six, and four years old, and a seven year-old sister. After going to school ,for a few years and learning to speak some English, he got a job early in 1969 as an interpreter with a group of ten marines who made up a C.A.P. team in his village. Lots of Vietnamese children attach themselves to such teams and are often well treated and affectionately looked after by the soldiers. When he had been working with them for 9 months, he was asked by a U.S. captain from the 19Bth Charlie Company, stationed near Chu Lai, if he would like to work for them. His pay would be $40.00 per month, paid in MPCs out of the pockets of the U.S. soldiers, plus his food and clothes. At the black market rate of exchange for MPC, plus his food and clothes, Vo-Han was as well off, if not better, than some of our highest paid limb-makers, and could enjoy a reasonable standard of living.

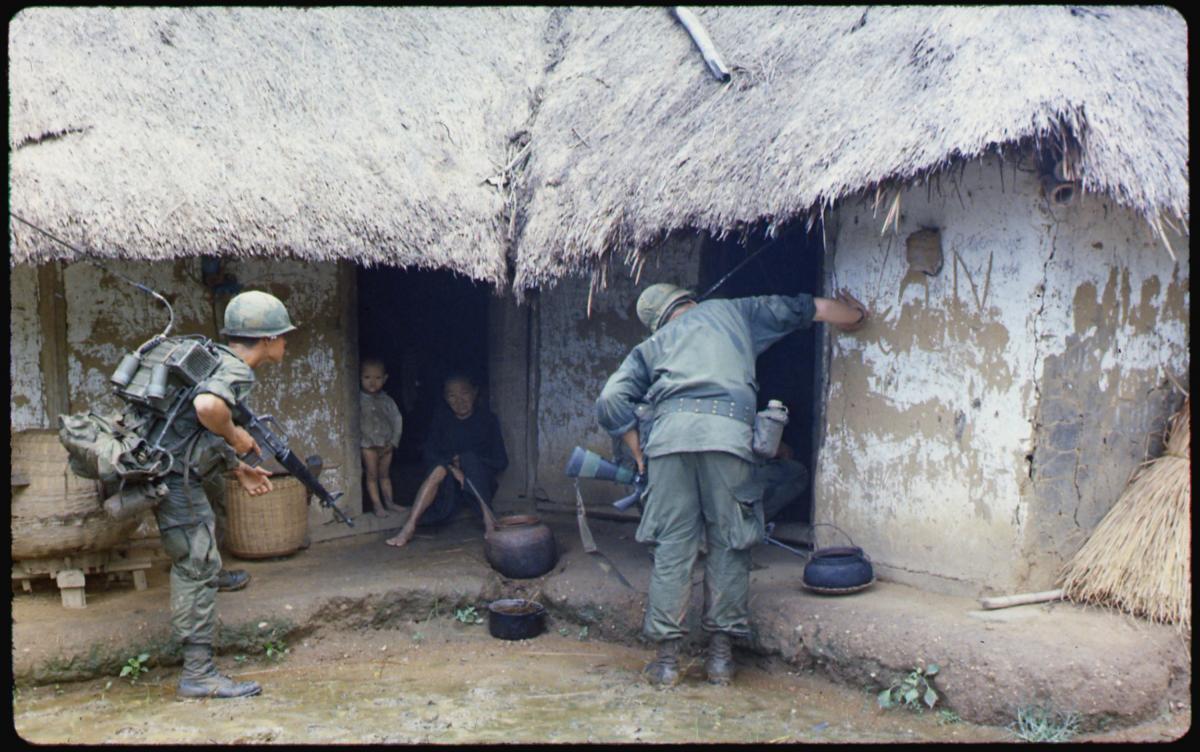

His job was to accompany the 198th when they went out on search and destroy missions to areas or villages that were well known VC strongholds or sympathetic to the NLF. In almost every case, the NLF had abandoned the village before the U. S and ARVN soldiers got there, leaving behind only old people, women, and children, sometimes not even those. Vo-Han's job was to interrogate these people, ask them where the NLF soldiers had gone, where their supplies were, where the booby traps and mines were laid, etc.

|

|

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons |

One day, last October, Vo-Han went with Charlie Company into the hamlet of Son Hoa (Son-tinh district, between National Route 1 and Son My). They entered from three different directions. Vo-Han was with the first platoon, and when he got into the hamlet, he turned off to one side to check out an area for booby traps and mines. He found one all right an M14 mine, and it blew both his legs off. He was taken by helicopter to Chu Lai military hospital, and operated on. His right stump has not yet healed, and the knee joint is still in a mess. Keith and I began to ask him for a few more details of his work:

Q. What sort of clothes do you wear when you go out on patrol?

A. I wear these man, U.S. Army uniform.

Q. Do you have a steel helmet?

A. Yes, but it’s too heavy, so I just wear a hat.

Q. When you question the villagers about the VC, do they talk?

A., Sometimes.

Q. If they don’t what do you do?

A., You know boxing? Well I do beaucoup boxing. I kick their ass, man. They talk.

Vietnamese people number (expletive) ten.

Q. But some people never talk; What do you do then?

A. You know monkey? Well we make monkey of them, and we kick their ass good.

Keith and I were confused at this point; we didn’t know what "monkey" meant,

but Vo-Han explained. A person who is stubborn in answering questions is hung

up by the arms from a convenient tree and beaten until he or she talks.

Q. Do you ever kill anyone like this?

A. No, we don't kill anyone.

|

|

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons |

Q. When you were wounded, what would have happened if the VC had got to you before the Americans? (This was a loaded question. I wanted to find out what sort of protection was given to these children under such circumstances. But the answer we got was another surprise.

A. I kill the (expletive) VC, man, I got beaucoup weapons.

Q. What sort of weapons?

A. I got M-16 (U.S. Army issue automatic rifle), twenty-one magazines, and three grenades.

Q. You can shoot the M-16?

A. Sure, man, 'course I can shoot the M-16. I can shoot (expletive)

Q. What will you do when you get your new legs?

A. I'll go back to Charlie Company.

Q. What will you do if the Americans leave Vietnam?

At this point Vo-Han looked at me as if I had lost my reason.

A. The Americans no leave Vietnam, man, they got beaucoup aircraft, bomb, napalm,

M-49; they not go until they kill every (expletive) VC. VC number ten

Q. But many American soldiers are leaving already, don t you know that?

A. The Americans no leave Vietnam until every (expletive) VC dead

At this point Vo-Han seemed to get fed up with talking to us. I got the impression he though we were very naive. He had none of the quiet good manners of a normal Vietnamese child his age, and he left us propelling himself away in his wheelchair.

Vo-Han has been fairly well looked after by the U.S. soldiers since he lost his legs. They have visited him regularly, given him money for cigarettes and extra food, etc. However he will get no compensation or pension from either the Vietnamese Government or the U.S. Government. He was a mercenary, and must accept the consequences. He is crippled for life, has no trade or profession, and must rely upon the handouts given to him by U. S. soldiers. The soldiers of Charlie Company no doubt will be quite generous to him whilst they are here. But one day Vo-Han will be on his own. The soldiers he places so much trust in will go home and. he will become a subject of conversation only when a few veterans get together over a beer, and swap stories about the Nam War.

Vo-Han gives the impression of being tough, sturdy, and self-reliant, but if you observe him for a while, you realize that he is---a child, frightened, unsure of his future, refusing to think what life would be like without Charlie Company.

I know of two other children with Charlie Company, one is eleven, and the other twelve. I don’t know their stories, but I have a good idea what may be waiting for them in the future. How many other children are there in Vietnam being employed by the U.S. Army? What will happen to them if they get their legs blown off, or blinded, or paralyzed, protecting the American soldiers for $40.00 a month? If they are killed, then this is very simple. They are buried, and in many minds, forgotten. If they live, they are an embarrassment. I realized this when I observed the reaction of the captain and the soldiers who brought Va-Han into, our centre. They felt ashamed, and so they should. I want the story of Vo-Han placed on the desk of not only the AFSC, but also on the desk of any newspaper editor who has the guts to print it, and the desks of Ambassador Bunker, President Nixon, and P .M. Wilson.

I cannot vouch for the validity of the details of Vo-Han's story, I can only report it as it was told to me by him. What I can say, without fear of contradiction, is that children are being employed by the U.S. Army, that they are being taken out on active patrols, and that their role is to help protect the lives of Gl's.

I have two sons; the elder has just entered his eleventh year of life, but then he is white, and has round eyes, and the GI’s out here would no more think of taking him out on patrol than they would their own children. We may not be able to stop the war out here, but I think if we move quickly we can put a stop to this disgusting practice and perhaps save the future and even the lives of a few children in Vietnam.