CPS Unit Number 004-01

Camp: 4

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: MCC

Opened: 5 1941

Closed: 5 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 625

-

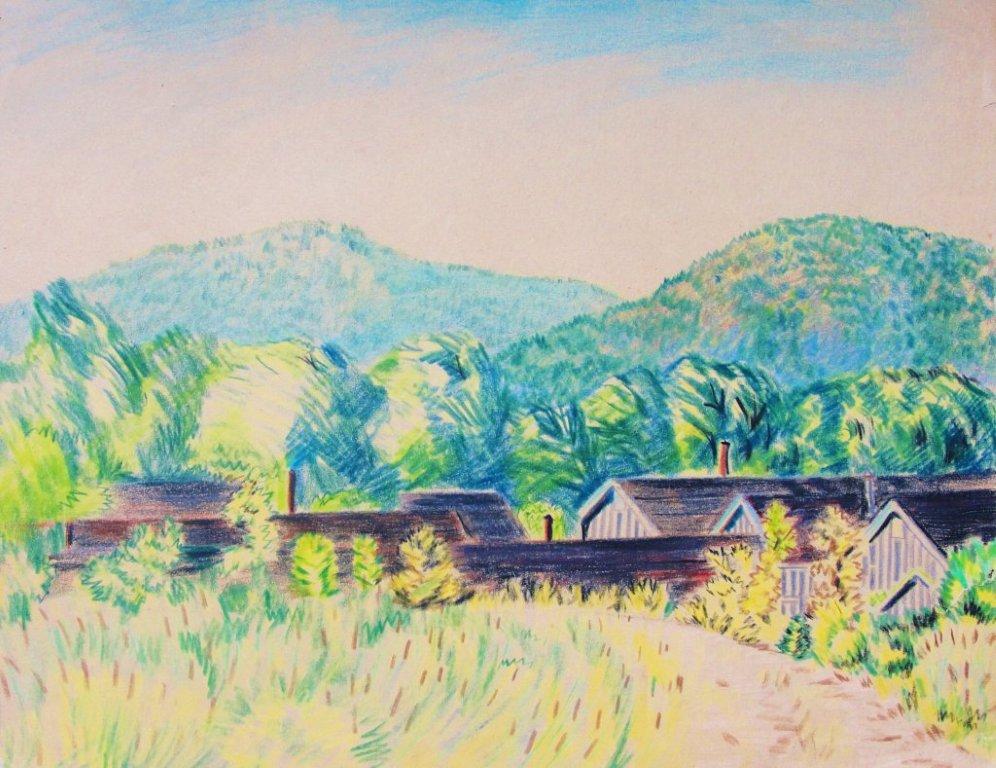

CPS Camp # 4 Grottoes, VirginiaThe Grottoes CPS CampDrawing by John Klassen, submitted by son Paul.

CPS Camp # 4 Grottoes, VirginiaThe Grottoes CPS CampDrawing by John Klassen, submitted by son Paul. -

CPS Camp No. 4, Grottoes, Virginia.Three men peeling potatoes. David Hess and two others sit outside the kitchen and dining hall.Digital image, Photo #43. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 4, Grottoes, Virginia.Three men peeling potatoes. David Hess and two others sit outside the kitchen and dining hall.Digital image, Photo #43. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 4, Grottoes, Virginia.Civilian Public Service field work. Persons left to right (not including persons on truck): R.D. Rhodes, Jay Farmwald (night watchman), Lloyd Schlabach, ?, ?, Ernie Detweiler, ? Landis Martin, Linford Drupp. Christ Yoder and two others on the truck.Digital image, Photo #35. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 4, Grottoes, Virginia.Civilian Public Service field work. Persons left to right (not including persons on truck): R.D. Rhodes, Jay Farmwald (night watchman), Lloyd Schlabach, ?, ?, Ernie Detweiler, ? Landis Martin, Linford Drupp. Christ Yoder and two others on the truck.Digital image, Photo #35. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp # 4, Grottoes, VirginiaDressing chickens. Left to right: ?, Ammon Stoltzfus, Mary Emma Showalter (dietitian), ?, and Charles Walters. Outside kitchen and dining hall, preparing for camp meal.Photo # 44. Box 1, Folder 85. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp # 4, Grottoes, VirginiaDressing chickens. Left to right: ?, Ammon Stoltzfus, Mary Emma Showalter (dietitian), ?, and Charles Walters. Outside kitchen and dining hall, preparing for camp meal.Photo # 44. Box 1, Folder 85. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp # 4, Grottoes, VirginiaNine kitchen and dining hall staff with Sister Tena Wenger, dietitianPhoto # 25. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive.

CPS Camp # 4, Grottoes, VirginiaNine kitchen and dining hall staff with Sister Tena Wenger, dietitianPhoto # 25. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive. -

CPS Camp # 4, Grottoes, VieginiaThree men working on a dam below the camp for emergency water.Photo # 24. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp # 4, Grottoes, VieginiaThree men working on a dam below the camp for emergency water.Photo # 24. Box 1, Folder 8. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

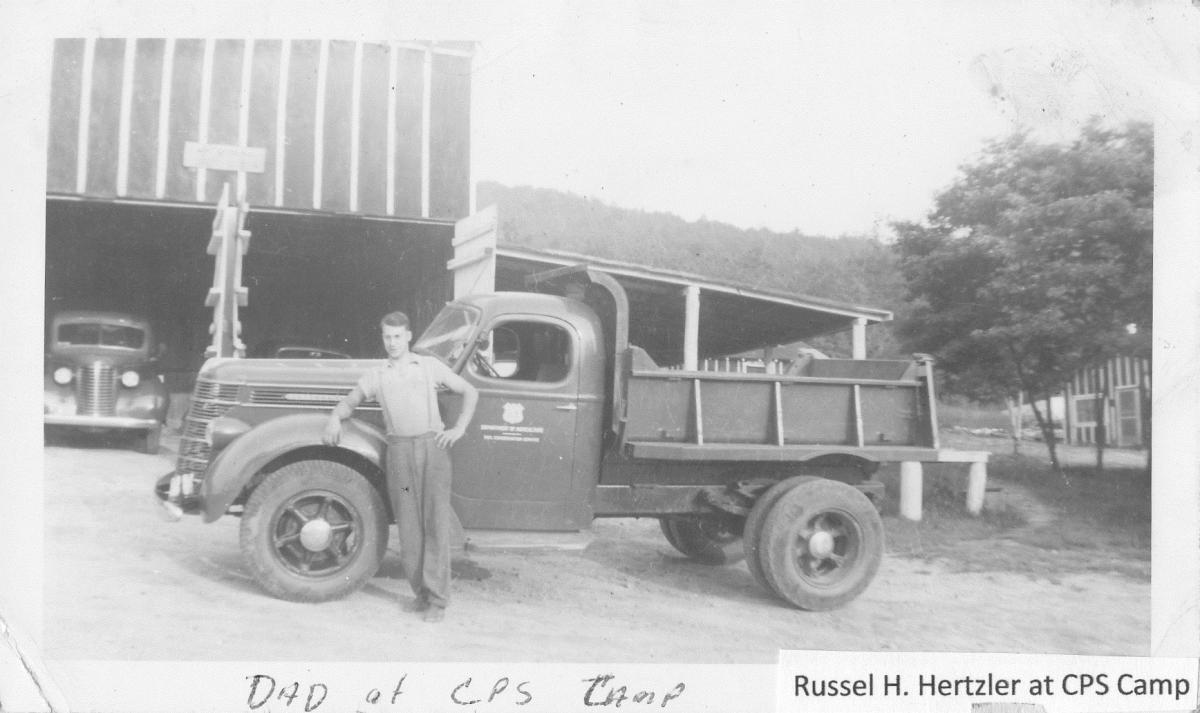

Russell Hertzler with Truck

Russell Hertzler with Truck -

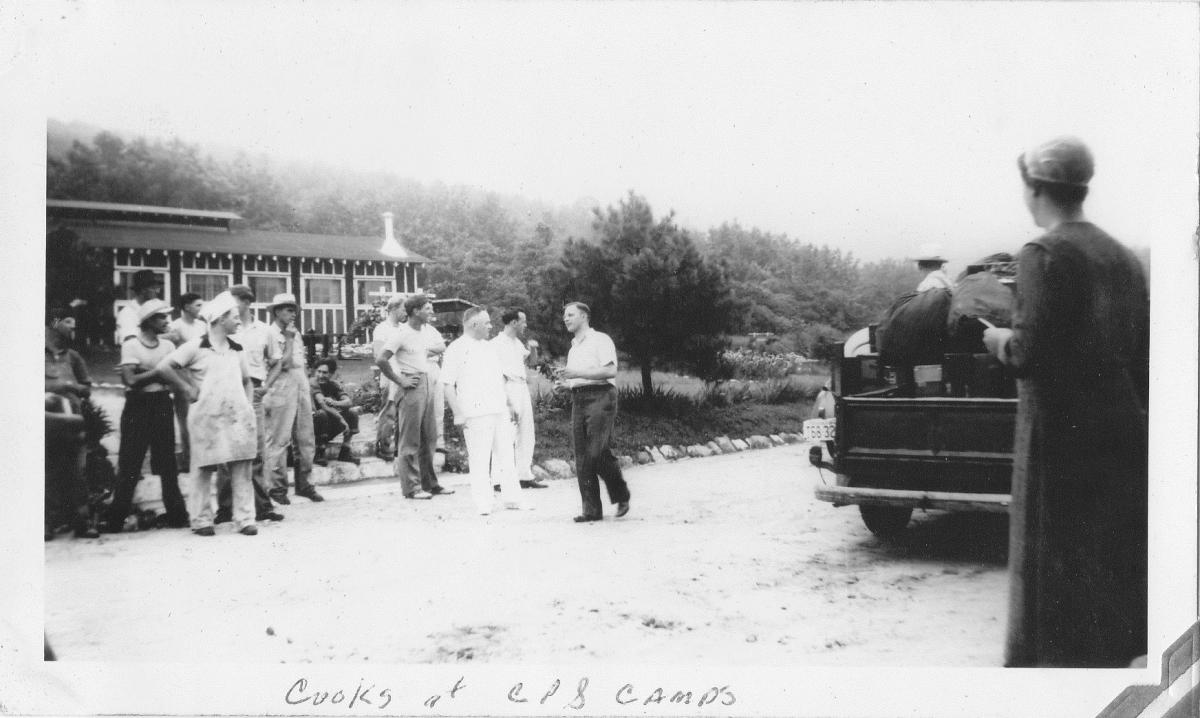

CPS Camp Cooking Staff

CPS Camp Cooking Staff -

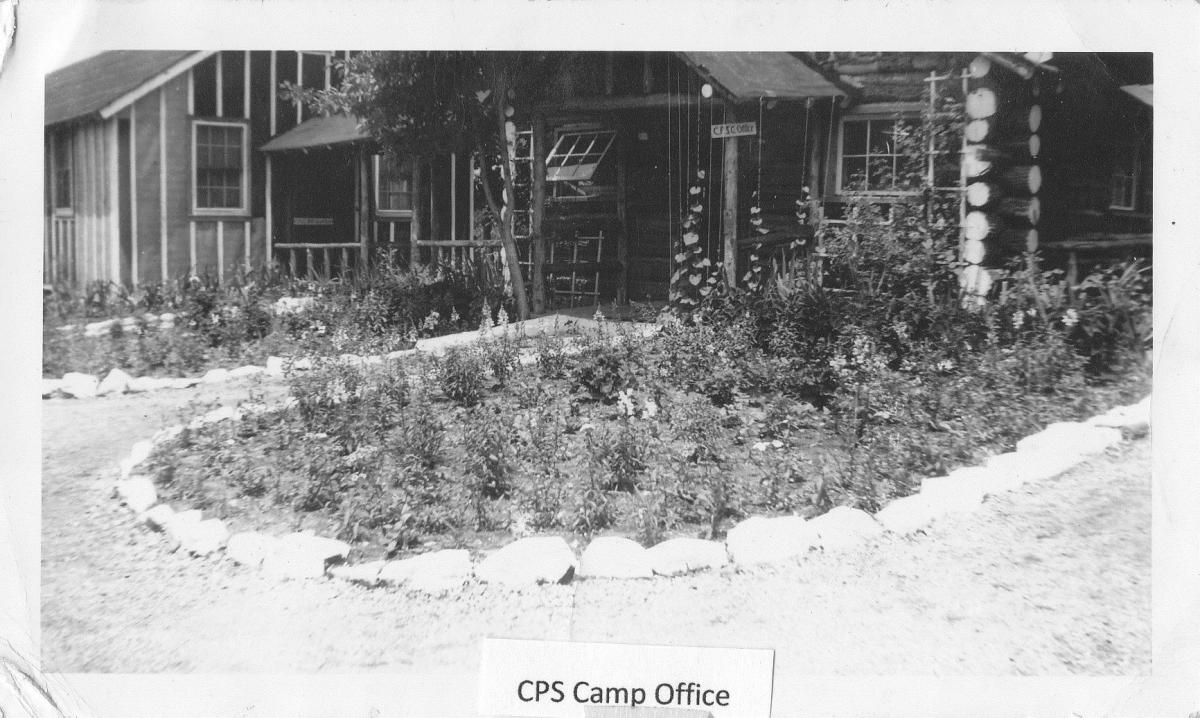

CPS Camp Office

CPS Camp Office -

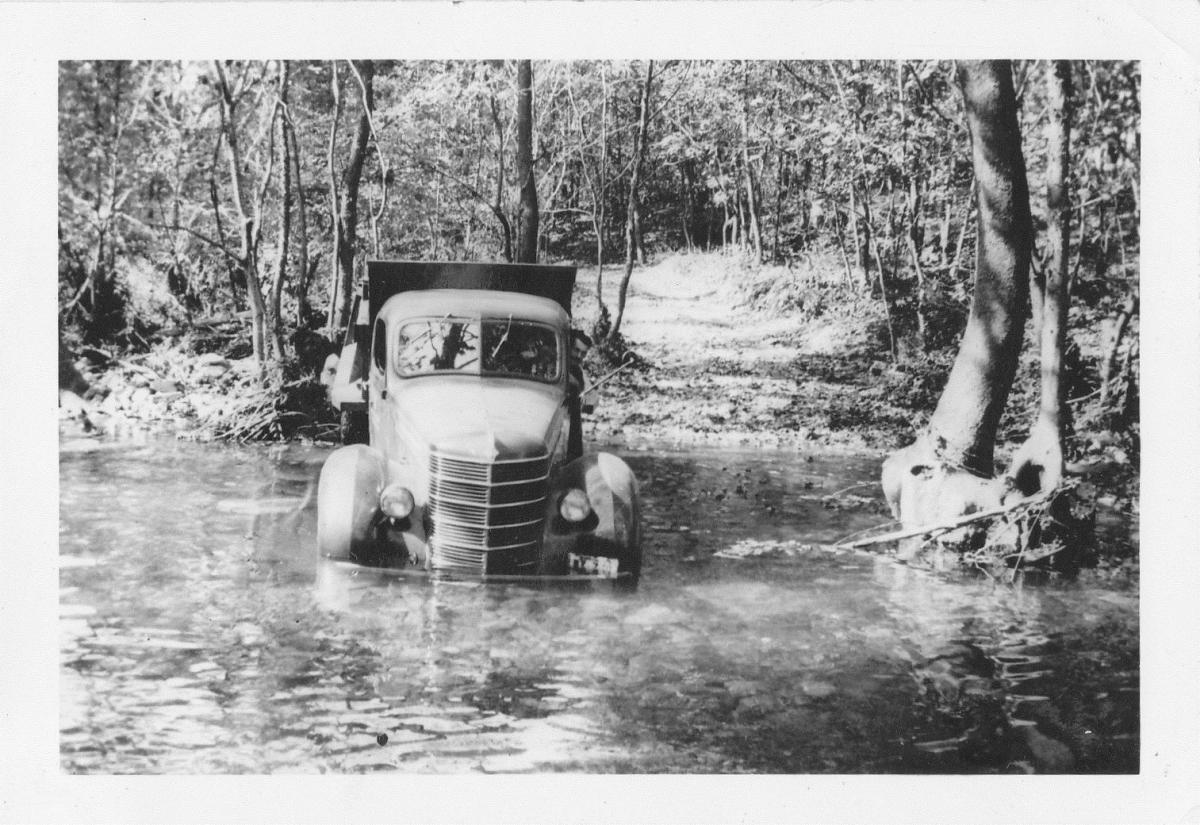

Driving through high water at CPS Camp 4

Driving through high water at CPS Camp 4 -

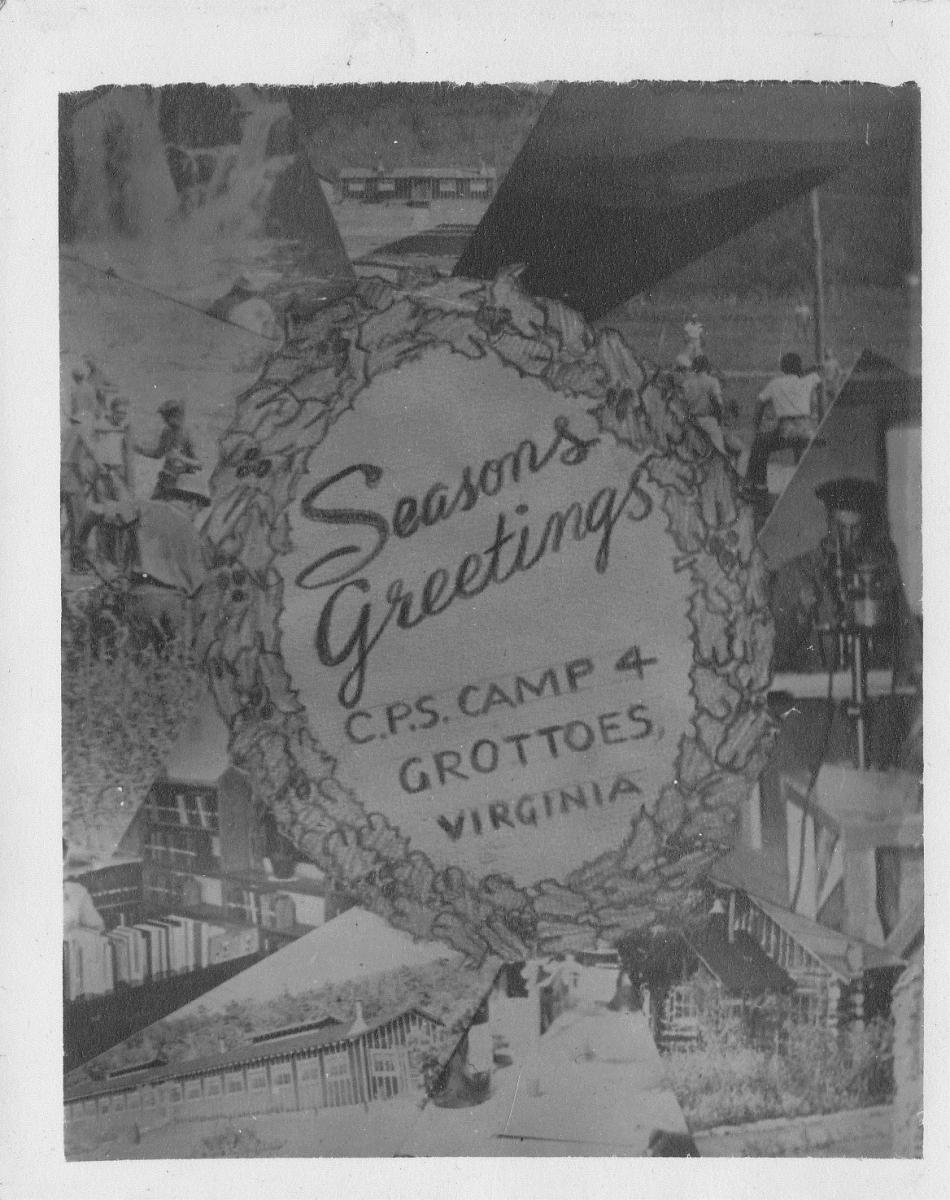

Grottoes Christmas Card

Grottoes Christmas Card -

High Water at CPS Camp 4

High Water at CPS Camp 4 -

Men of CPS Camp 4

Men of CPS Camp 4 -

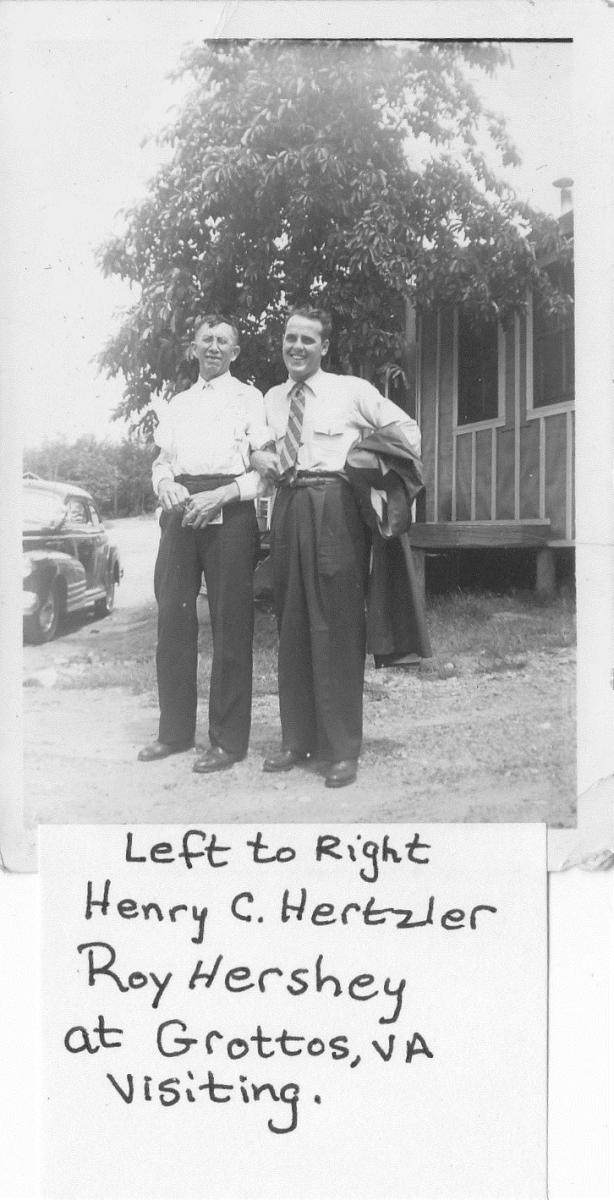

Russell Hertzler's Dad Visiting

Russell Hertzler's Dad Visiting -

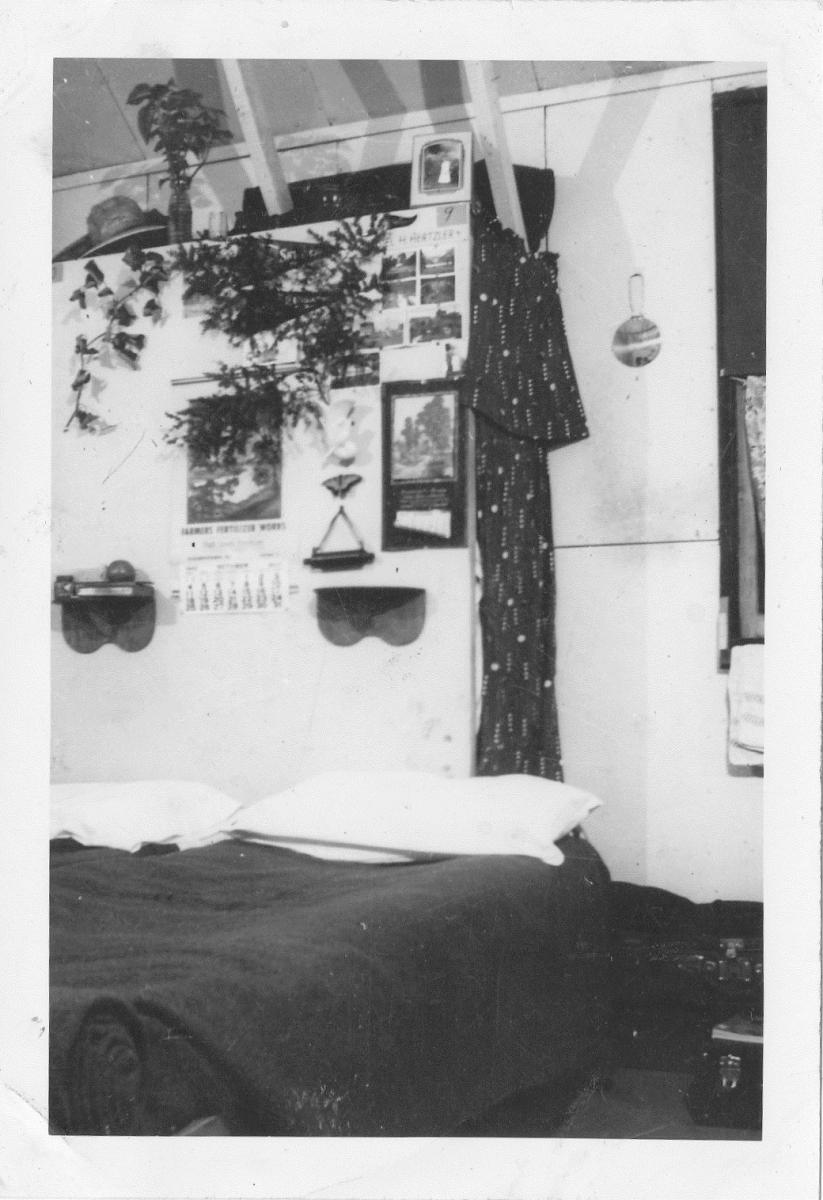

Sleeping Quarters of Russell Hertzler at CPS Camp 4

Sleeping Quarters of Russell Hertzler at CPS Camp 4

CPS Camp No. 4, a Soil Conservation Service base camp, was located three and a half miles east of Grottoes, Virginia, just outside of Shenandoah National Park. Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) opened the camp in May 1941and closed it in May 1946. CPS men cleared pasture lands, stabilized gullied banks and performed other work to halt soil erosion.

The camp was located on the lower slope of Austin Mountain and at the eastern entrance to Brown’s Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains, just outside the boundary of Shenandoah National Park. The camp was five miles from Skyline Drive. It had served previously as Civilian Conservation Corps Camp NP-4, and consisted of four barrack dormitories, a large dining room, offices, staff quarters and other buildings. In Rockingham County, Grottoes is part of the Harrisonburg Metropolitan Statistical Area, just off of US Highway 340.

Directors: John Mosemann, Jr., Paul Bender, Emmanuel C. Hertzler, Vincent Krabill, Francis Smucker

Cook: Lena Wenger

Dietician: Mary Emma Showalter, Myrtle Schnell Hertzler, Wilma Hess, Naomi Weber

Matron: Ruth Mosemann, Mrs. Paul Bender

Nurse-Matron: Tena Heinrichs

One hundred-fifty assignees served at this first MCC operated camp. The men represented the most homogeneous of the larger base camps—most were from the eastern states, from conservative communities and Mennonite groups. The majority of men in Mennonite camps reported farming or other agricultural work as their occupations when entering CPS. Men in Mennonite operated camps reported on average 10.45 years of education at point of entry into CPS. (Sibley and Jacob p. 171-72)

Nearly half of the topsoil had wasted away and the land was eroded by deep gullies in the once fertile Shenandoah Valley west of the camp. CPS men cleared pasture lands, stabilized gullied banks, planted thousands of seedlings, removed and constructed miles of fence, laid much drainage tiling, built diversion ditches and dams for farm ponds. One man was stationed in a fire-lookout tower; many man days were spent fighting fires.

Since the camp had been neglected, Vernon Schmidt of Harper, Kansas began in mid January to serve as watchman and oversee repairs and maintenance. An MCC Advisory Committee, representative of the Mennonite groups in the eastern United States, helped guide plans for the camp. They later visited to meet with staff, talk with the men, and make recommendations to the Mennonite Central Committee.

Ruth Mosemann served as matron at the camp while Joe Brunk served as business manager and took charge of purchasing equipment and major repairs for the camp. The camp included a hobby shop, a kiln, chapel, and classrooms.

Letters of welcome to the men laid out goals that “a spirit of true Christian comradeship, genuine mutual understanding, and sincere cooperation might prevail in all camp relations”, for work, study and activity, and included a list of provisions to bring to camp. (Gingerich p. 97) Upon arrival the men received a physical examination for baseline health information and were vaccinated for smallpox and typhus.

The camp organized around committees—Camp Council, Religious Activities, Social and Recreational, Buildings and Grounds Maintenance, Subsistence, Safety, and Olive Branch newspaper. The goal was for the camps to provide “excellent training in democratic living”. Emmanuel C. Hertzler, reflecting on his experience years later, recalled a decision he made as camp director while at Grottoes.

. . .the CPS men were so eager to make the camp programs successful that it was possible to talk out our solutions. One decision that I made alone taught me a long remembered lesson. The buildings at Grottoes had been built and used by the Civilian Conservation Corps and had a sound system that linked the office to the dormitory buildings. On my own I decided to pump music in the dorms in the evenings. When I played recordings of well know hymns I heard only a few comments but when I added Mozart and Beethoven the comments became cries for peace and quiet. The conservatives were not ready for my music. I wished that I had been more considerate. (in “Detour. . .Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories p. 25.)

A Camper’s Manual described facilities, opportunities and provisions available at the camp (e.g. barbershop, hospital, library and reading room, laundry, prayer room, photography darkroom and more).

The first issue of Olive Branch appeared in October 1941 and the last in February 1946. Considered consistently of high quality, the Olive Branch not only contained good coverage and well written articles, but also excellent art work.

In general the people in the farm communities around the camp proved friendly. Camp men held prayer meetings in many homes, assisted with many services such as taking the sick to the hospital, helping at funerals, and making telephone calls. In May 1943, a four-year-old girl became lost in the woods and a large crew of CPS men engaged in a comprehensive search for her. After five days, one of the campers found her alive on a rocky slope. He stayed with her while two other campers hiked nearly five miles for help to complete the rescue. The local papers gave credit to the CPS men for their major share in the search.

The camp hosted special conferences. In January 1943, a two-day Bible conference led by ministers focused on the Book of Philippians. On the first weekend of March 1943, Paul Mininger of Goshen College gave inspirational talks on the topic “Youth Faces Life”.

A six-week cooking school began in April and was conducted by Mary Emma Showalter, camp dietician. She trained twenty men from different Mennonite camps for relief work cooking and as camp cooks.

The following summer Professor J.P. Klassen of Bluffton College directed a ten-day art institute on clay modeling and pottery making as well as charcoal drawing. He lectured on his experiences as a CO in Russia during WWI. In subsequent visits he encouraged wood carving and sketching.

A three-day conference for business managers and dieticians brought talks by Elizabeth Hernley, Edna Ramseyer, John M. Snyder, Ray Schlichting and others.

In June 1944, the Grottoes camp had named one of the men to be trained as a project assistant. This person assisted both the camp director and the work supervisor and organized on-going orientation and training programs for men in various aspects of the camp work skills, policies, and organization. In general the program devoted an hour per week to speakers, films and other education to promote greater understanding and skill in conservation work.

The men celebrated each camp anniversary with a special dinner, program, speeches, readings and clever diplomas.

Ministers visited the Mennonite camps. Titus M. Books, an ordained minister of the Brethren in Christ Church performed pastoral work at the Grottoes and three other camps beginning in July 1943.

For more information on camp work, life and programs see Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA 1949, Chapter IX pp. 95-107.

For personal stories of CPS men, see Peace Committee and Seniors for Peace Coordinating Committee of the College Mennonite Church of Goshen, Indiana, “Detour. . .Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1995, 2000.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.