CPS Unit Number 027-01

Camp: 27

Unit ID: 1

Operating agency: BSC

Opened: 3 1942

Closed: 12 1946

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 72

-

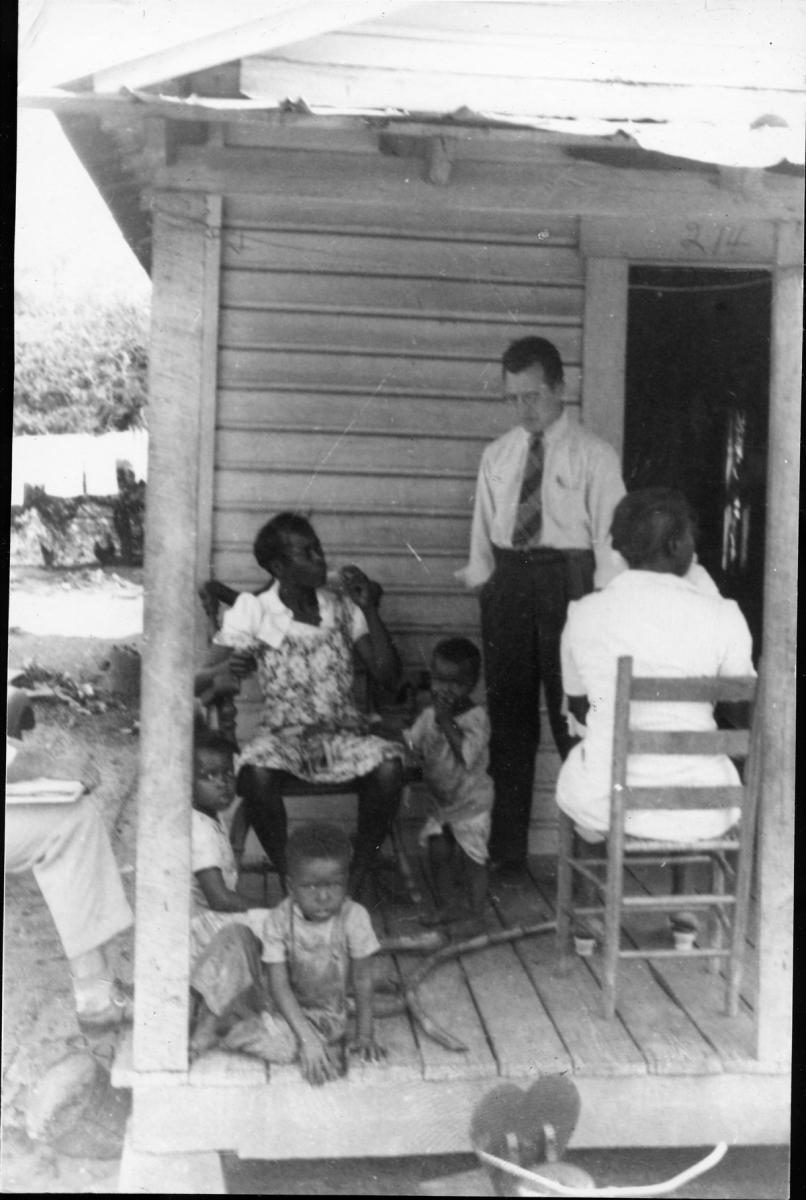

CPS Camp No. 27, Florida State Board of Health, Subunit 2, Mulberry, FloridaWilliam Yoder talks over sanitation problems with his friends on sanitation survey.Digital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansas

CPS Camp No. 27, Florida State Board of Health, Subunit 2, Mulberry, FloridaWilliam Yoder talks over sanitation problems with his friends on sanitation survey.Digital Image at Mennonite Church USA Archives, North Newton, Kansas -

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 1, Crestview Florida.Leaving Camp Crestview site Nov. 12, 1943.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.Nov. 12, 1943

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 1, Crestview Florida.Leaving Camp Crestview site Nov. 12, 1943.Digital Image © 2011 Brethren Historical Library and Archives. All Rights Reserved.Nov. 12, 1943 -

CPS Camp No. 27 Mulberry, FloridaCamp 27, Mulberry, Florida. The oxen and cart that drag many a log to the sawmill.Photo #47. Box 1, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 27 Mulberry, FloridaCamp 27, Mulberry, Florida. The oxen and cart that drag many a log to the sawmill.Photo #47. Box 1, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 27 Mulberry, FloridaCPS Camp No. 27, Mulberry, Florida. Ed Zehr and Pete Bartel leveling group around completed unit [sanitary privies].Photo #152. Box 1, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 27 Mulberry, FloridaCPS Camp No. 27, Mulberry, Florida. Ed Zehr and Pete Bartel leveling group around completed unit [sanitary privies].Photo #152. Box 1, Folder 17. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

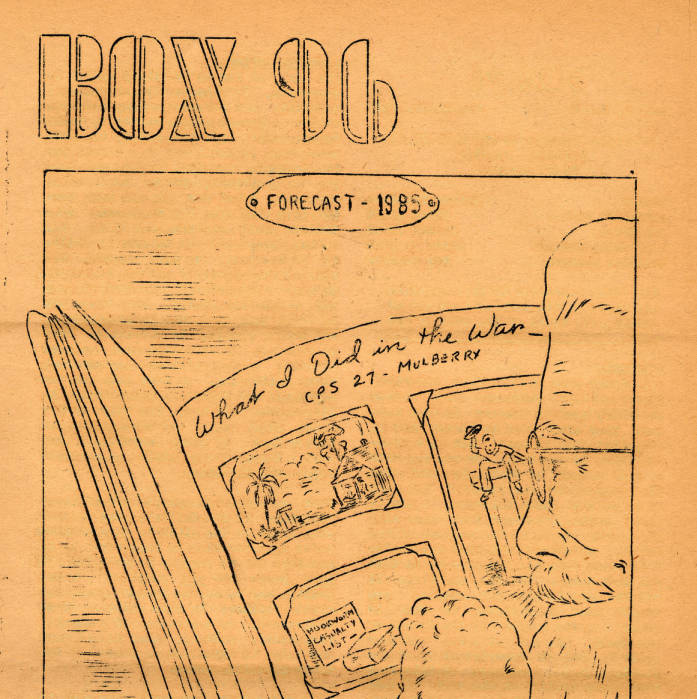

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 2, Box 96Box 96 was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 27, subunit 2, from April 1944 to March 1945.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 2, Box 96Box 96 was a newsletter published by the men at Camp 27, subunit 2, from April 1944 to March 1945.Digital Image from American Friends Service Committee: Civilian Public Service Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

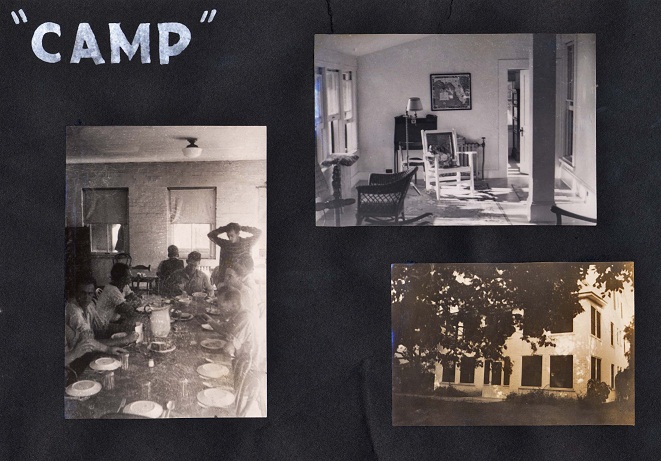

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #6.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #6.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #7.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #7.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

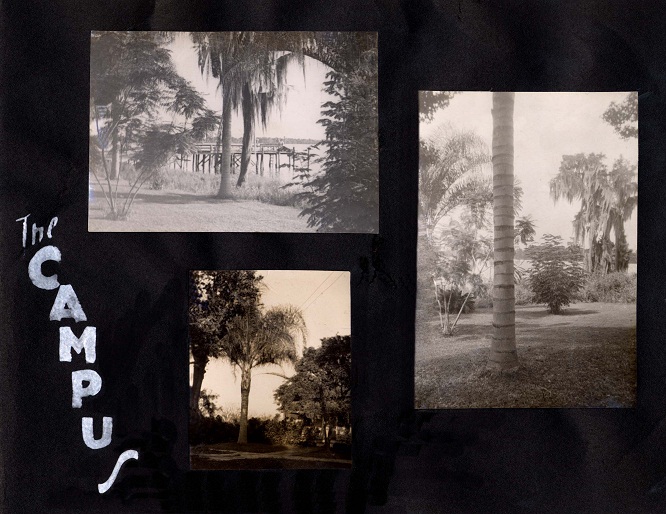

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #3. "The Campus".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #3. "The Campus".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

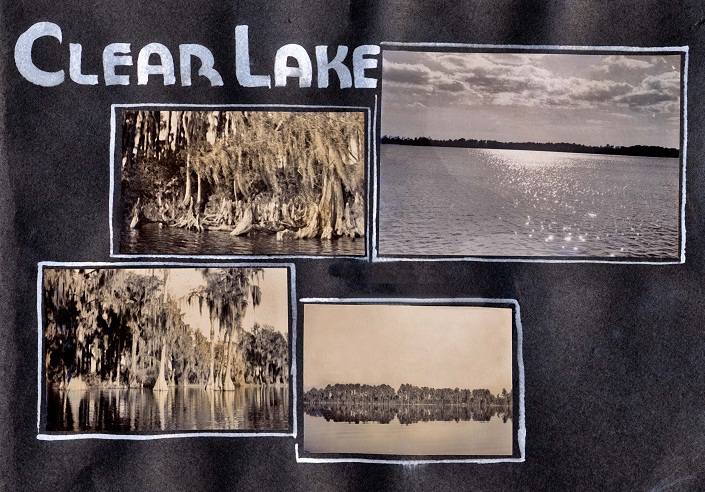

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #4. "Clear Lake".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #4. "Clear Lake".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

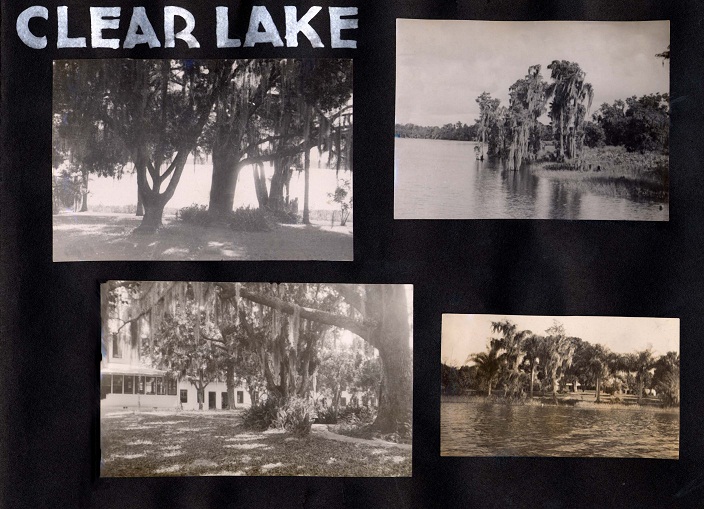

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #5. "Clear Lake".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #5. "Clear Lake".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

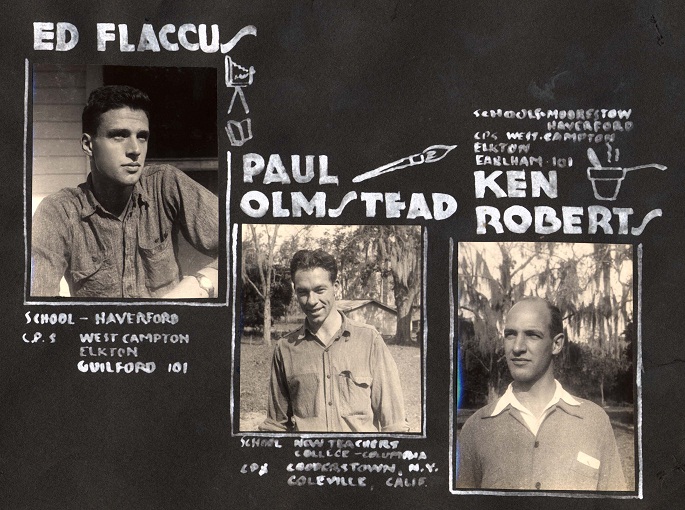

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #10. Edward Flaccus, Paul D. Olmstead, Kenneth S. Roberts.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #10. Edward Flaccus, Paul D. Olmstead, Kenneth S. Roberts.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

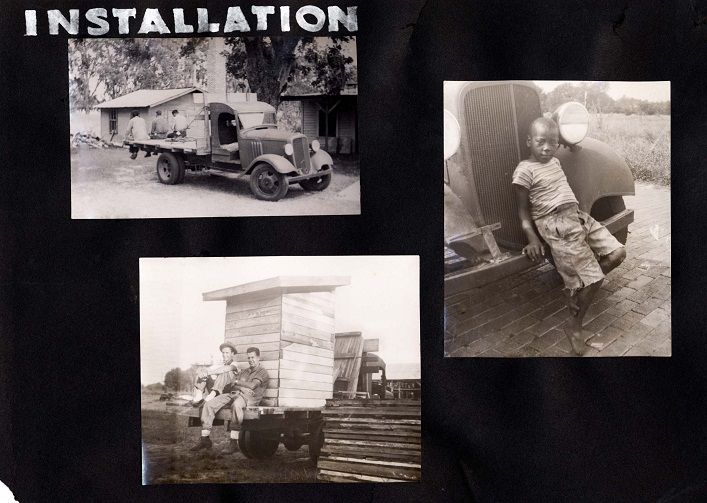

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #14. "Installation".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #14. "Installation".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

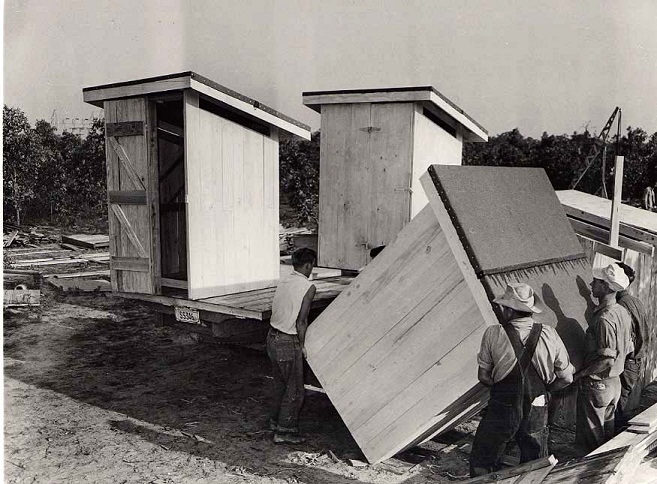

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Loading latrines. Credit: Tony Garnet.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Loading latrines. Credit: Tony Garnet.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

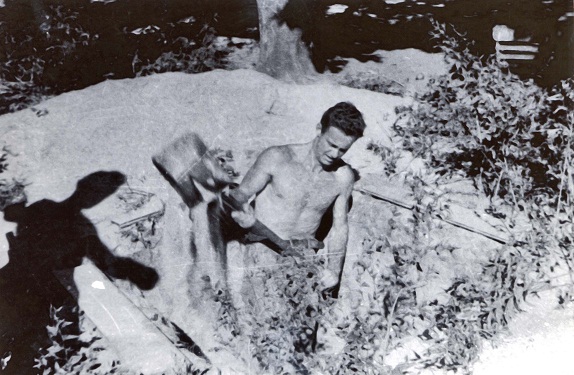

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Agricultural work. Orlando, Florida.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Agricultural work. Orlando, Florida.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

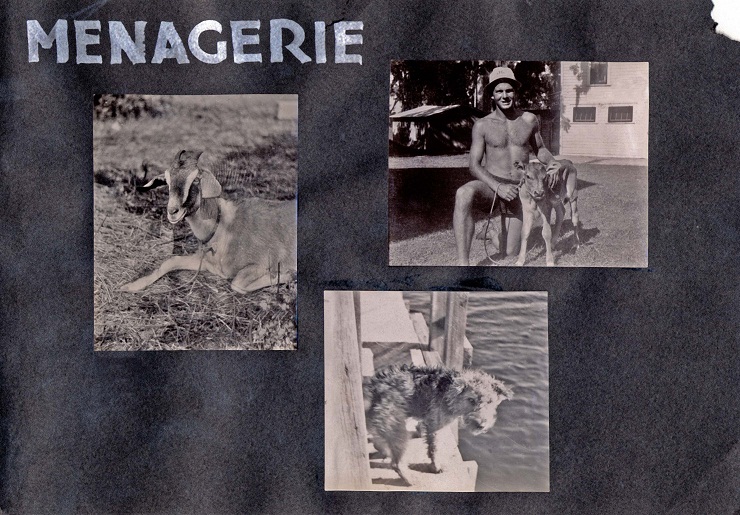

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #8. "Menagerie".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #8. "Menagerie".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

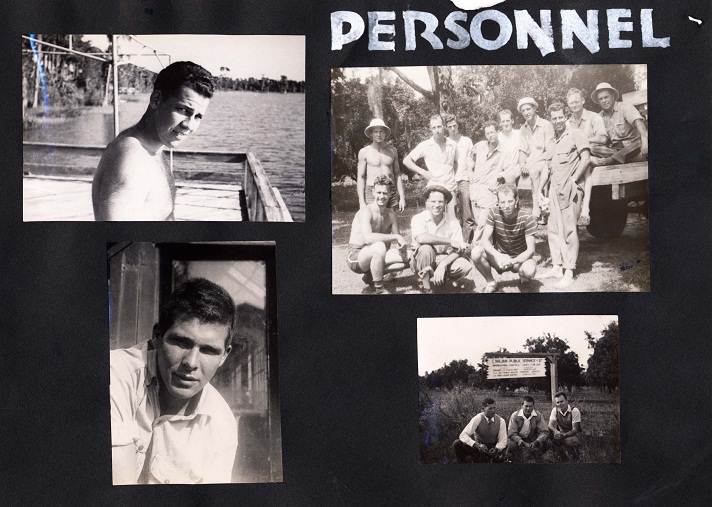

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #9. "Personnel".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #9. "Personnel".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

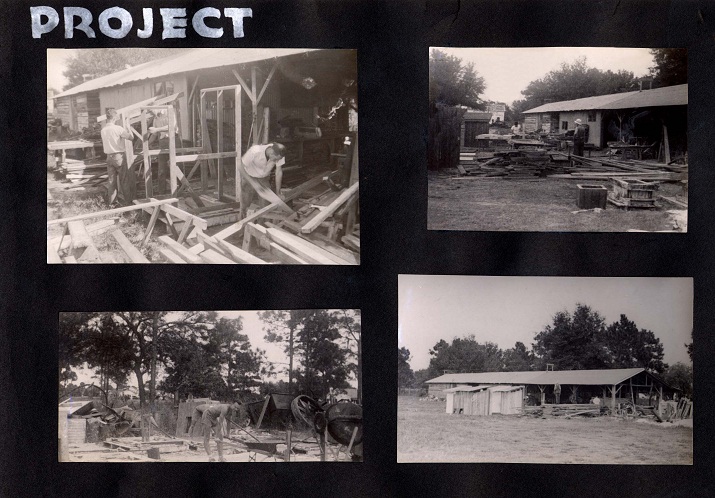

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #13. "Project".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #13. "Project".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

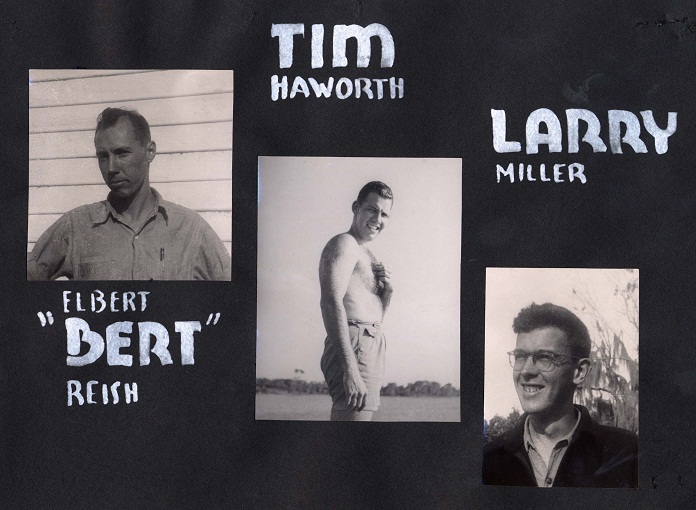

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #11. Joseph Elbert Reish, Timothy P. Haworth, Lawrence L. Miller.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #11. Joseph Elbert Reish, Timothy P. Haworth, Lawrence L. Miller.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

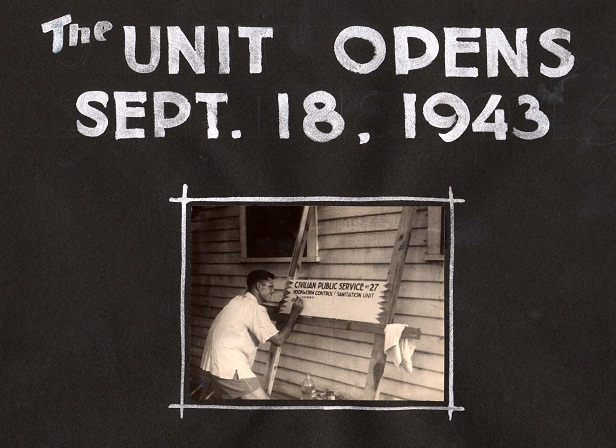

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #1. "The Unit Opens, Sept. 18, 1943".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #1. "The Unit Opens, Sept. 18, 1943".Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

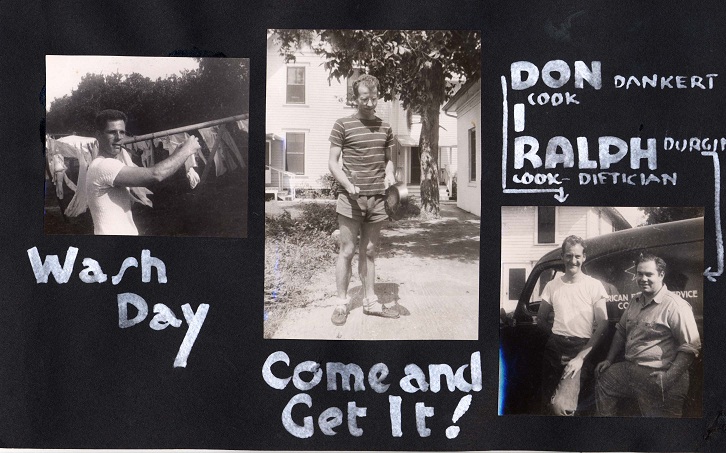

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #12. Donald A. Dankert and Ralph P. Durgin.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania

CPS Camp No. 27, subunit 4Photo album of Orlando, Florida, project, page #12. Donald A. Dankert and Ralph P. Durgin.Digital image from American Friends Service Committee: CPS Records (DG002), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania -

Group of conscientious objectors at CPS Camp # 27Group of conscientious objectors at Civilian Public Service Camp No. 27, Mulberry, Florida, January 1944, during World War II, with visiting ministers Ernest E. Miller and M.C. Lehman. Front row, left-right: 1. Herman Ropp, 2. George Bohrer, 3. Arthur Thiessen, 4. Ethan Horst, 5. Jacob Guhr, 6. Edwin Weaver, 7. Dr. Ernest E. Miller Back row, left-right: 1. Ernest Pankratz, 2. Harold thiessen, 3. William Yoder., 4. Delman Stahly, 5. Dennis Lehman, 6. Lester Hiebert, 7. John Horst, 8. M.C. Lehman, 9. Wesley Prieb, 10. Paul Schmidt, 11. Galen Widmeer, 12. Menno Lohrenz, 13. Willard Baer, 14. Paul Milelr, 15. Roland Bartel, 16. Ernest Shank, 17. Franklin Wiebe, 18. Roland Kauffman, 19. Leo Goertz, 20. Mrs. Harold Martin, 21. Harold Martin, 22. C. Nelson Hostetler Not on picture, but part of group: Peter Bartel, George Falb, Hugh Hostetler, Mervin Hostetler, Dwight Jacobs, Dallas Voran, Harry Weirich, Edmund Zehr, Martin Schroeder, Albert BohrerMennonite Central Committee Historical ArchivesJanuary 1944

Group of conscientious objectors at CPS Camp # 27Group of conscientious objectors at Civilian Public Service Camp No. 27, Mulberry, Florida, January 1944, during World War II, with visiting ministers Ernest E. Miller and M.C. Lehman. Front row, left-right: 1. Herman Ropp, 2. George Bohrer, 3. Arthur Thiessen, 4. Ethan Horst, 5. Jacob Guhr, 6. Edwin Weaver, 7. Dr. Ernest E. Miller Back row, left-right: 1. Ernest Pankratz, 2. Harold thiessen, 3. William Yoder., 4. Delman Stahly, 5. Dennis Lehman, 6. Lester Hiebert, 7. John Horst, 8. M.C. Lehman, 9. Wesley Prieb, 10. Paul Schmidt, 11. Galen Widmeer, 12. Menno Lohrenz, 13. Willard Baer, 14. Paul Milelr, 15. Roland Bartel, 16. Ernest Shank, 17. Franklin Wiebe, 18. Roland Kauffman, 19. Leo Goertz, 20. Mrs. Harold Martin, 21. Harold Martin, 22. C. Nelson Hostetler Not on picture, but part of group: Peter Bartel, George Falb, Hugh Hostetler, Mervin Hostetler, Dwight Jacobs, Dallas Voran, Harry Weirich, Edmund Zehr, Martin Schroeder, Albert BohrerMennonite Central Committee Historical ArchivesJanuary 1944

-

-

Nov. 12, 1943

Nov. 12, 1943 -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

January 1944

January 1944

CPS Camp No. 27 Subunit 1, a Public Health Service project opened at Camp Crestview in March 1942 and was administered by the Brethren Service Committee. It moved to Tallahassee in November 1943 and the unit closed in December 1946. The men constructed and installed sanitary privies to prevent soil contamination, since hookworm eggs carried in the excreta of infected persons contaminate the soil.

This special project responded to assignee desires to address human needs. It opened in Camp Crestview on a small plot of six acres where the CPS men lived.

The “hookworm belt” of the South had been designated “of greatest need” since the disease had been controlled and eliminated through simple medical and sanitary measures when coupled with effective education. Eradication of hookworm disease contributed to improvement in health standards as well as economic and social well being.

After the unit moved to Tallahassee, the men constructed a new camp on Forest Service land in the Apalachicola National Forest, made possible through a tri-party agreement among the camp, the Florida State Board of Health and the U.S. Forest Service.

Directors: Ralph Townsend, Philip Nordstrom, Virgil Wilkinson

In Brethren camps, the men when entering CPS tended to report a mix of religious denominational affiliations, with about half citing Brethren affiliation.

Men in Brethren camps also reported on entry into CPS a variety of occupations, with twenty-nine percent citing farming and other agricultural work, eighteen percent technical and professional, and twenty-one percent business management, sales and public administration. On average, they had completed 12.22 years of education, with nearly forty percent having enrolled in or graduated from college, or enrolled in graduate or postgraduate work. (Sibley and Jacob pp. 171-72)

Twenty men were assigned to Crestview and thirty-eight to Tallahassee.

To confront hookworm disease, the men produced and installed inexpensive privies, built septic tanks, and dug deep wells.

The Crestwood CPS hookworm project constructed new wood privies, painted them, and then moved them to the appropriate location where a pit had been dug and completely cemented. Sanitary wells were dug and enclosed pumps installed on a concrete base, which eliminated the previous problems of contamination by rodents and other animals, surface water, and fly infestation. The third phase was to screen homes to attack an estimated 100,000 cases of malaria in Florida with an annual death rate of 340. (Kreider p. 20)

They improved the communities in other ways by painting and repairing schools, both for the schools attended by African-American students and those designated for white students. They built baby incubators and cribs.

The project occurred in cooperation with the Florida State Board of Health and the local county health departments. Assignees supervised the actual camp work. The men believed in the worth of the work and organized themselves to carry on not only project work, but also classes, meetings, recreation, formal and informal religious services, and assistance for neighboring families.

The men reported their main problems as lack of adequate transportation to get men and materials to the work sites coupled with scarcity of materials, and the uncertain tenure of the local county health department.

In spite of the progress, they did face “serious hostility” from the white establishment.

Using the power of the press, the editor of The Okaloosa Messenger editorialized against these “unpatriotic termites” and encouraged other opposition in his “Purely Personal” column, given a prominent position on the front page. A friend of the editor described a conscientious objector as a person opposed to any form of killing or fighting for the protection of his country, and went on . . .

Who invited or brought them here we do not know, although we have strong ideas. But one thing, of which we are sure, the people of Okaloosa County do not approve of this kind of project and camp. We do not believe that these men should be “chased or ran out”. That is not the American Way of Life. We also believe that there may be some of these men who are really sincere in their belief. . .

This objectionable site should be moved. We mean moved in an orderly manner. Moved like the Americans move people. Send them elsewhere. Let them go live and serve from whence they came. If they are natives of Pennsylvania or any other state, send them home! (Willie D. Douglas, The Okaloosa Messenger, [April 29, 1943] in Kreider p. 20)

Public pressure intensified, with a mother of four children serving in the military writing two weeks later:

What I believe slackers (self-styled Conscientious Objectors to be:

I believe them to be men of foreign nationality, educated, trained and organized by Germany. Sent to America to pose as a religious group for the purpose of winning their way into our religious organization[s] by preying on the sympathies of over-zealous Christian women. Their sole purpose is to undermine the morale of our young people, by sowing seeds of doubt and teaching them in their sly cunning way not to uphold our constitution and what it stands for. . .

If this is not the purpose, then why do they impose upon us by attending our churches? Even have the audacity to sit in our choirs, over which hangs a roster bearing the names of our boys in service. They know they are not wanted by 99% of the people. They know they are hated and despised. Do they care? No! That is their sacrifice for Hitler. Why are they not segregated like the Japs? They are no better. (Lilian Givens Weatherly, The Okaloosa Messenger, [May 13, 1943] in Kreider p. 21)

Ralph Townsend, Director of the hookworm project, wrote that he apologized for any embarrassment as the camp did not intend to offend anyone. However, with increasing pressure, the unit moved from Crestview to a location near Tallahassee.

During the time at Crestview, “the men spent 3,082 person days erecting and installing 577 sanitary privies . . .38 septic tanks were built, 31 houses were screened against the malaria-carrying mosquito, fifty sanitary wells were dug, and many other jobs done.” (Eisan p. 252)

The Tallahassee move permitted the camp to expand its goals to include assistance in establishing a more stable economy for people living in the area. The project extended its relationship to a tri-party agreement with the U. S. Forest Service, the Florida State Board of Health and the Brethren Service Committee to accomplish the logging and milling of lumber for privy construction. The arrangement included designing camp buildings, installing sawmill equipment, logging and milling the lumber for that construction as well. The camp bought the equipment necessary for the work—a 48-inch main saw, an edger and a planer. In exchange, the Forest Service allowed cutting timber from their lands at no cost.

After the construction, an equal number of men fought fires and performed prevention duties, while another group constructed and installed sanitary privies. The latter group also logged the timber, milled the logs as needed so that the project had a continuous supply of materials.

The men, organized into interest groups or committees to plan and develop the different aspects of camp life. A representative of each of the committees (worship, education, community service, social, recreation) met with staff to form the staff council. The council considered issues to determine what needed to be brought before all the men, and coordinated other activities. When a matter affected the whole camp, all in the camp met to participate in decision-making.

The Brethren Service Committee believed in meeting the individual needs of the campers in order to increase the awareness of interdenominational work and relationships.

In November 1943 the camp moved to Tallahassee, some one hundred fifty miles to the east after the local newspaper campaign to discredit local government officials who had consented to the establishment of the CPS unit in Crestview. While opposition to the presence of COs became public in the newspaper, all who had received help or assistance expressed their appreciation to the men. Many in the community were friendly, but the minority and public voice prevailed. Even the most vigorous critics, however, had no criticism about the personal conduct of the men.

Toward the end of the project at Tallahassee, even though the men were highly committed to the value of the work and the project, they began to chafe under the “restrictive features of the CPS system”—long periods of work without pay and compensation, the lack of choice for their manner of serving, as well as the freedoms of everyday living.

The men published a camp paper Crestviews, which published its first issue in March 1942 and continued through March 1943.

For a full discussion of hookworm control, leadership and cooperation among agencies, cooperative leadership among the campers in the camp, see Leslie Eisan, Pathways of Peace: A History of the Civilian Public Service Program Administered by the Brethren Service Committee. Elgin, IL: Brethren Publishing House, 1948, Chapter 8 pp. 273-295.

For stories from men who, as COs, walked to a different drummer during World War II, see Mary R. Hopkins, Editor, Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Caye Caulker, Belize: Producciones de le Hamaca, 2010, Harold Blickenstaff, pp. 233-246.

See also J. Kenneth Kreider, A Cup of Cold Water: The Story of Brethren Service. Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 2001.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.