CPS Unit Number 141-01

Camp: 141

Unit ID: 1

Title: Mississippi State Board of Health

Operating agency: MCC

Opened: 2 1945

Closed: 3 1947

Workers

Total number of workers who worked in this camp: 70

-

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiCivilian Public Service camp 141, Gulfport, Mississippi. Surveying for terraces and ditches.Box 2, Folder 25. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiCivilian Public Service camp 141, Gulfport, Mississippi. Surveying for terraces and ditches.Box 2, Folder 25. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

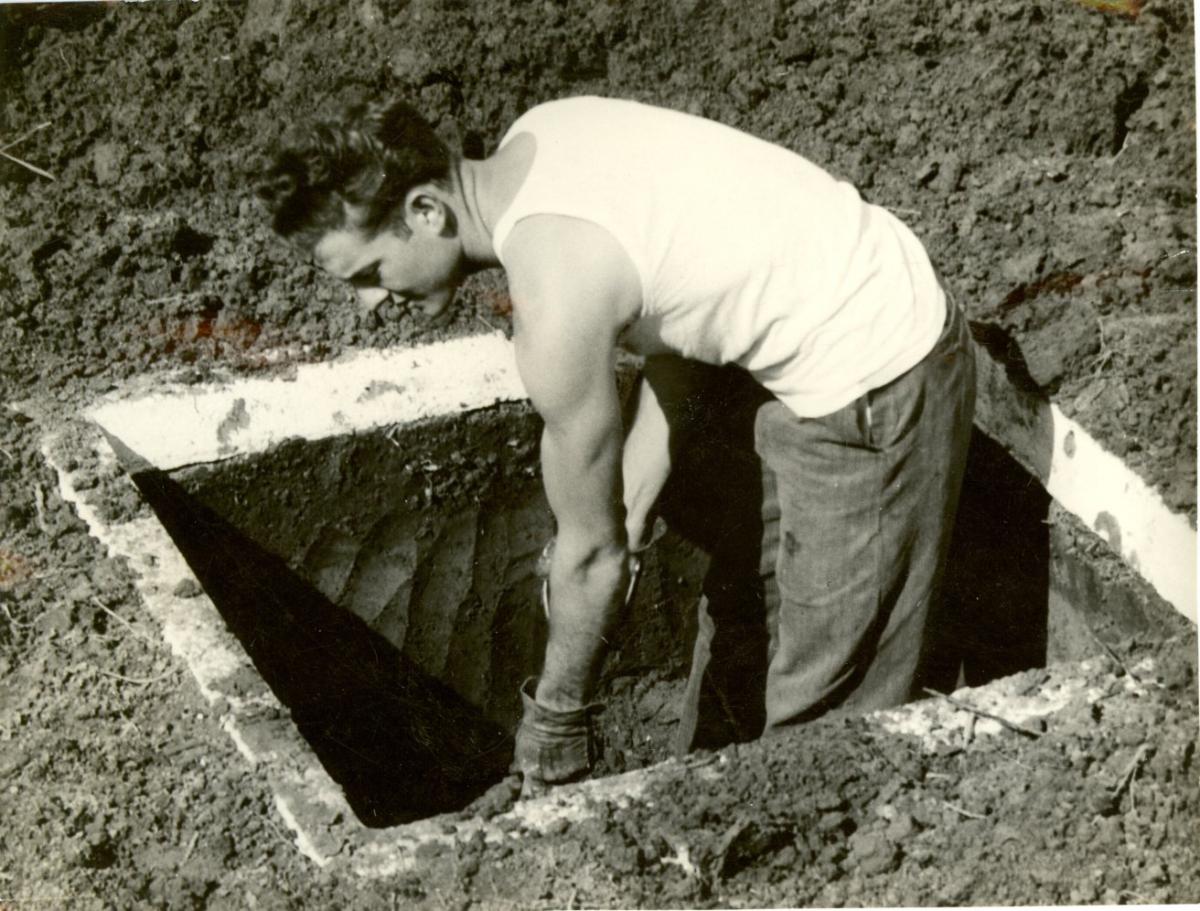

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiCivilian Public Service camp 141, Gulfport, Mississippi. Digging the privy pit on installation.Photo 266 Box 2, Folder 25. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiCivilian Public Service camp 141, Gulfport, Mississippi. Digging the privy pit on installation.Photo 266 Box 2, Folder 25. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiMaking the contact on the typhus control program.Photo 14 Box 2, Folder 25. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiMaking the contact on the typhus control program.Photo 14 Box 2, Folder 25. MCC Photographs, Civilian Public Service, 1941-1947. IX-13-2.2. Mennonite Central Committee Photo Archive -

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiHarry Lantz distributes rat poison for typhus control.From the private collection of Leo Harder, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5.1946

CPS Camp No. 141, Gulfport, MississippiHarry Lantz distributes rat poison for typhus control.From the private collection of Leo Harder, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5.1946

CPS Unit No. 141, a Public Health Service unit located at Harrison County Health Department in Gulfport, Mississippi and operated by Mennonite Central Committee, opened in February 1945. The men worked in hookworm control and education, conducted health surveys and testing as well as built, sold and installed privies. At the conclusion of the CPS program, Mennonite Central Committee continued a Voluntary Service unit in the community.

Gulfport, Mississippi, an important southern terminus of the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad, was a relatively prosperous industrial and shipping center. The CPS unit was located four and one-half miles north and one-quarter mile east of Gulfport in a camp previously used for relocation of transients, then operated by the Girl Scouts.

Just outside the city limits between the camp and Gulfport rested North Gulfport, an unincorporated community with unpaved streets, lack of a water or sewage system, run-down houses in contrast with conditions in Gulfport. North Gulfport was essentially an all black community whereas Gulfport was white, except for several pockets of blacks. Jobs, restricted along racial lines, contributed to poverty in North Gulfport and in the surrounding rural areas. The Camp Bernard CPS unit would serve both poor whites and poor blacks.

Claude Shotts, of the NSBRO Special Projects Section, had traveled through Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia to investigate possibilities for CPS units that would work to control environmental diseases. Since the Mississippi State Board of Health had been interested in establishing a CPS Public Health unit in the state, they approached the governor. Serious sanitation problems in Harrison County accompanied by high incidence of hookworm disease contributed to its designation as an area of greatest need. Harrison County officials expressed their interest, and Shotts worked with leaders to plan a public meeting to discuss the potential for locating a unit there, since conscientious objection was not a popular idea in the South. Because the Florida public health units had run into public opposition, NSBRO wanted to carefully check out a site and plan for the introduction of a CPS unit.

Representatives of the Chamber of Commerce, the American Legion, the public schools, the mayors of Gulfport and Biloxi, representatives of the state and county health departments, as well as the United States Public Health Service and the press, all gathered on August 24, 1944. After full discussion, they unanimously agreed in principle to establish a project in Harrison County. The following month, the Board of Supervisors contacted the local trade union council to seek approval, which was granted.

On September 15, 1944, the Harrison County Board of Supervisors officially requested a CPS unit for Harrison County. The State Board of Health concurred and requested that Selective Service authorize such a unit.

Shotts had learned that public officials “spoke highly of the Mennonites who live in Southern Mississippi,” and inferred that public relations should be good. He had already discussed possibilities with Orie O. Miller, Executive Secretary of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), who agreed to send a representative to Harrison County as soon as Selective Service approved a unit.

Harry Martens, the MCC eastern states regional director, went to Mississippi to meet with representatives of the United States Public Health Service, the Mississippi State Health Department, the Harrison County Health Department, the Harrison County Board of Supervisors and the NSBRO on November 28 and 29. The meeting yielded a statement of understanding of the responsibilities of each of the cooperating agencies for the operation of the unit. This covered assignments from the Harrison County Health Department, rent for housing facilities, equipment and power tools, camp administration, as well as establishing standard prices for privy construction and installation. Martens and local officials agreed to establish a revolving health fund to support project activities, with the expectation that upon the eventual closing of the camp, remaining monies would be used for “the promotion of health activities in Harrison County” upon closing of the camp. (Gingerich p. 238)

Martens was advised by the United States Army colonel who accompanied him as he made contacts in the community, to give special time to area ministers to interpret the convictions of CPS men, since many religious leaders were openly hostile to conscientious objectors. The minister contacted to arrange the meeting demonstrated the challenge when he deplored the foolish position of COs during a national emergency. Harry Martens later reported in a letter that the colonel asked the minister if he didn’t preach about loving God and fellow human beings. Though he confessed disagreement with the position of conscientious objection, the colonel said “These men try to put into practice what you ministers have been and are preaching. They refuse to kill. Is that wrong?” The minister retorted, “That’s different; we’re in a war now.” (Letter to Harold Regier, March 29, 1977 in Haury p. 2)

In preparation for the unit arrival, crews made improvements to the camp—installing screens for windows and doors, patching roofs, repairing steps and doors, installing lockers, clearing trash from the grounds, opening sewer lines, and removing debris from the bottom of the pond. Camp Bernard, named for a nearby bayou, was surrounded by tall pines. An artesian well over 600 feet deep on the grounds furnished drinking water.

Directors: Harold Marten, Melvin Funk

Dietician-Matron: Myrtle Schnell Hertzler

Matron: Esther Miller

Nurse-Matron: Margaret Reimer

The unit was approved for forty men. In the first phase, MCC selected nineteen men from one hundred and eight applications for transfer from other CPS camps and units. One of the applications described the complex motivation of those who, near the end of the war, applied for transfer to Gulfport.

We have talked much about Americans living under adverse and unfortunate circumstances in the suburbs of our cities and certain rural areas, but we have been able to do very little about it. By promoting the cause of health and working for improvement of sanitary conditions we may be striking at the base root that makes for many adverse and unfortunate circumstances referred to heretofore. We are looking forward to having the Mississippi project serve as an open door to greater Christian service in our own country. (1944 Application for Mississippi Public Health Project in Haury pp. 3-4)

Over the life of the camp, nearly seventy men served. They entered CPS from sixteen different states. Some of the men were married, some with families who followed them to the camp.

The overwhelming majority identified eleven different Mennonite group affiliations when entering CPS (Amish Mennonite, Brethren in Christ, Conservative Amish Mennonite, Church of God in Christ Mennonite, General Conference, Independent Mennonite, Krimmer Mennonite Brethren, Mennonite Brethren, Mennonite Church, Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonite). Two men reported Methodist affiliation and one Christadelphian.

On average, men in MCC camps and units had completed 10.45 years of education, twenty-two percent having completed some college or all four years, or some graduate work. (Sibley and Jacob, p. 171)

Of the forty-one men at the camp in early 1946 who indicated their occupation at point of entry into CPS, nineteen reported “farming”, and nine “student”. (Haury pp. 8-9)

During the summer of 1946, eight women joined a voluntary service unit based at Camp Bernard and worked in the community. They not only taught Bible school in both the black and white communities, but also conducted supervised play at designated hours on playgrounds in the Jim Crow South. Others joined later in the summer and continued on into the fall, remaining longer than the summer unit women. A second women’s summer unit came for the summer of 1947.

The project, designed to improve health conditions in Harrison County, also provided an opportunity for men to engage in relief work in the community. As such the unit was described as “relief work at home”, as compared to foreign relief training for work abroad. High standards crafted for admission stressed the same standards stated for foreign relief training units.

As word of the new Gulfport unit spread throughout existing locations, controversy arose, especially in some of the camps administered by the American Friends Service Committee and the Brethren Service Committee. In particular, CPS assignees wanted to know if the new unit would be “freely interracial or Jim Crow”.

Seventy-one men from CPS Unit No. 80 in Lyons, New Jersey, a Brethren mental hospital unit, wrote NSBRO objecting to Shotts’s statement that, “As far as I know there has been no CPS project either in the south or the north where there had been advance agreement that men will be received without race distinction. It is exceedingly unfortunate that we cannot carry out religious ideals on race along with our religious convictions about war.”

The Lyons men feel strongly that by failure to address “the race question the NSB is not accurately representing the concerns of the historic peace churches. They also feel that to live consistently we can tolerate no condition short of equality for all, and that if we do accept such conditions we are making a deal with the race-baiters and are denying the basic Christian principle of Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of men.” (Box 96, [March, 1945] p. 2 in Gingerich p. 259)

The writer of the above article, from the public health camp at Mulberry, Florida, argued that the Gulfport unit should be opened regardless of racial politics, since “We do not agree that if we cannot have an ideal arrangement-- in this case racial equality—at the outset, we should stay out. We do not agree that more good can be done by refusing to go into such a situation than by going in and trying to improve conditions by working on the local scene.” His conclusion was that by carrying out a health program serving both races equally while demonstrating with small acts belief in the brotherhood of man, more could be accomplished toward addressing the problem than not opening a camp in the South. (Gingerich p. 259)

The camp opened in February 1945. As a first project, the men installed sanitary facilities at a Boy Scout camp near Biloxi, since it was without water or sewage systems and the toilets were inadequate. Heavily utilized, Wilkes Camp affected the health of many.

The coordinated effort to address hookworm disease and other sanitation problems began with a door-to-door survey conducted by James Rineer to obtain information on excreta disposal, water facilities and screening. If he discovered that the family had no toilet, he attempted to sell them a new $30 sanitary privy. If the family was unable to buy one, he attempted to sell a base unit for $9 upon which they could construct their own toilet facility. By the fall of 1945, he had made 1,200 calls and found that 63 percent of those contacted had unsanitary toilet facilities and 9 percent had no toilet facilities at all. (Gingerich p. 261, Haury p. 6)

On CPS assignee at Gulfport offered an educational program in the community, showing health films to Boy Scout groups and other organizations throughout the county.

Some of the men created materials for hookworm education. One drafted maps to identify areas with unsanitary conditions.

A team devoted primary effort to the construction and installation of sanitary privies. Men prefabricated the privy bases of cypress for durability, a concrete slab with riser, made the walls and seat of pine, and topped the unit with a corrugated roof. The men hauled the units to the site by truck, where they dug the hole and affixed the parts to erect the privy. The first privy was installed on June 14, 1944.

By March 21, 1946, the men had installed 319 privies and visited 1,442 homes. Privies cost $30, which covered the materials only, since CPS men were not paid for their labor. Any receipts over expenses were returned to the revolving health fund for direct health programs of Harrison County Public Health.

In the second stage, men contacted students directly in the schools. “During the first year, the Camp sent 3,319 letters to children and spoke to 3,744 children in school.” The men also operated a laboratory which ran tests for hookworm and other diseases. “During this same period they performed 2,983 blood tests for syphilis, 1,080 tests for other venereal diseases, 1,953 tests for intestinal parasites, 358 chest X rays, and 211 diphtheria cultures. Responding to the results of these tests, they made 233 visits to homes of hookworm victims and delivered 347 packages of hookworm medicine.” (Report on Health Related Activities, April 1, 1945 to March 31, 1946, in Haury, p. 6)

The CPS men worked with the County Health Department on several special projects, including a rat-poisoning campaign to control typhus, spending 349 person days on this effort. The laboratory also conducted tests in milk sanitation.

Margaret Reimer, the camp nurse hired on a full-time basis as one of the county nurses, (her salary contributed to the special health revolving fund), visited homes in her part of Harrison County. She routinely made visits to all maternity homes of infants and preschool children. On one occasion “she discovered children and pigs eating from the same dish.” Encountering often overwhelming conditions, she noted, “It leaves a person helpless. There is so little you can do outside of teaching them health habits and talking to the parents, except remember them in prayer to our Lord, who so perfectly understands the hearts of children, that he might somehow give them a better life.” (Letter from Margaret Reimer to Albert Gaeddert, December 26, 1945 in Haury p. 7)

Every other Saturday night, young and old from the community gathered at Camp Bernard for an evening of games, educational films and refreshments. The men also engaged members of the community in toy repair and building projects.

The men held church services at the camp. A number attended Gulfhaven Mennonite Church and participated in its program. Once a month, the church and the camp held conjoint services either at the camp or the church. One of the CPS men was ordained to the ministry in the Gulfhaven Church and settled permanently in the community. Others attended the Methodist church. Men also helped at other Mennonite churches in Des Allemands and Akers, Louisiana.

In their after work hours, CPSers took on projects to improve the North Gulfport black school. They refitted windows, replaced broken panes, built-in a new cupboard in the kitchen, stopped chimney leaks, and painted the ceiling. The men and women also showed educational films on health and other subjects at the schools, erected playground equipment, and promoted shop classes for boys of the North Gulfport area.

In many contacts with families, the men found opportunities to witness as noted below.

“How much do you fellows make if you don’t mind saying?”

“Well, it’s like this, we don’t receive any pay. We are drafted conscientious objectors to war. We do not believe it is right to kill, so we have volunteered to do constructive work for the country instead. The government graciously allows us this privilege but doesn’t grant any pay.”

“You don’t receive any pay? That doesn’t seem right. Why they pay the German prisoners 80 cents a day. . . . Here is a dollar apiece for you men.”

But the two men kindly refused as they were not in the habit of receiving tips.

“Goodbye, and if you fellows ever get a chance, stop in to see me and stay for a meal too.” (Christian Service in the South, Summer Issue, 1945 in Gingerich p. 261)

At some point during the life of the camp, a number of men assisted an Amish community with a barn raising.

Emmanuel C. Hertzler, who served as laboratory director for the Harrison County Board of Health Laboratories and also coordinated the laboratory studies of the CPS project, reflected on his experience nearly sixty years later.

My experience in studying parasites during my university days had prepared me for microscopic identifications, but nothing had prepared me for the devastating effect that these organisms had on people.

I had some fears of going to the South because I supposed I would be working for and with antagonistic militarists. Imagine my surprise to see that our CPS project and we, the CPS workers, were warmly welcomed.

When the State Director of Public Health learned that I would be opening the Gulfport laboratory without a good microscope he took me to his stock of new instruments in the State Capitol building. He told me to take my pick and so I obtained two brand new, extraordinarily good microscopes for our new laboratory in Gulfport.

Contrary to my earlier fears I never was exposed to an angry or cross word in all my days in Mississippi. Myrtle served as matron and dietician at the camp and was involved in many of the crucial decisions that were necessary to make a bare bones camp a home away from home. She had a way of pleasing campers. (“Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories p. 24)

The men at Gulfport published Christian Service in the South beginning with the Summer 1945 issue.

Near the end of the unit, as the war had drawn to a close and a number of the original group of men had been discharged, the average age dropped as did the level of educational attainment. In addition, the decline in morale at the end of the war was found at Gulfport as well as at other units.

When MCC began the camp at a time the war was nearing the end in Europe, they considered that Gulfport might be a site for continued service to the community and society in partnership with churches. The VS Summer Service units tested the model of serving poor blacks and whites in the South. By February 15, 1947, MCC acted to recognize the Gulfport Unit as an official Voluntary Service Unit that would continue after the close of CPS into the 1960s. In this way, the Gulfport unit served as an early model for other Mennonite voluntary service units that opened in both rural and urban areas in the two decades following the Second World War.

For more information on the work, life and programs in Mennonite public health camps, see Melvin Gingerich, Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee printed by Herald Press, Scottdale, PA 1949, Chapter XII 252-275.

For more information on women COs see Rachel Waltner Goossen, Women Against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941-47. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

For more information on the Gulfport CPS unit and its continuation as a voluntary service unit after the war, see David A. Haury, The Quiet Demonstration: The Mennonite Mission in Gulfport, Mississippi. Newton KS: Faith and Life Press, 1979.

For general information on CPS camps see Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. Intercourse, PA: Good Books 1990.

For personal stories of CPS men, see Peace Committee and Seniors for Peace Coordinating Committee of the College Mennonite Church of Goshen, Indiana, “Detour . . . Main Highway”: Our CPS Stories. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1995, 2000.

See also Mulford Q. Sibley and Philip E. Jacob, Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-47. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Camp periodicals database.